|

| Monk in the Lama Temple, Beijing, photo Luise Guest |

|

| Hutong Doorway |

I have spent the last few days seeing the "big sights" under clear blue skies, hoping to persuade my husband (initially dubious) of the delights of Beijing. I am not sure whether I have succeeded on that score, but walking on the Great Wall at Mutianyu is always a memorable experience, as is the Forbidden City, the Lama and Confucius Temples, the Drum and Bell Tower, and the remaining hutongs.

The artists I have met, the people I have encountered, the extraordinary juxtapositions, contrasts and contradictions of a society in great flux - all so memorable and so unlike anywhere else in the world - will continue to astonish me every time I think about my time here.

In the meantime, here is an extract from my article about my encounter with the very extraordinary Bingyi Huang in her converted Yuan Dynasty temple in Beijing, published on The Culture Trip

Between Heaven and Earth:

Bingyi's Meditative Ink Paintings

With a new international interest in contemporary interpretations of Chinese ink painting, reflected in the number of exhibitions in major museums and galleries around the world, the practice of brush and ink has caught the attention of the international art market. But for Chinese artist Bingyi Huang it remains deeply personal and meditative, a means of reaching the sublime

|

| Bingyi's brushes, photo Luise Guest |

In the tradition of Chinese ink painting, which most art historians agree began during the Tang Dynasty, the artist’s aim was to capture the spirit of the subject, rather than to create a realistic representation, or likeness. Today, discussions about ink painting are at the centre of global discourses about contemporary art in China, and the practice itself is in flux.

James Elkins, in his essay ‘A New Definition of Contemporary Ink Painting’, describes this highly contested and increasingly controversial form as ‘a Chinese art practice with an unparalleled density, complexity, and historical depth of reference…ink painting connects to a tradition that has been traced back to Han dynasty (206 B.C. – A.D. 220) tomb reliefs, and even to cave paintings and the decorations on Shang( ca. 1600 – 1050 B.C.) bronzes...No other genre of Chinese image making draws on such significant history or requires so much knowledge and experience on the part of the viewer.’ He goes on to make the point that his is not a visual description, nor an account of a method of making. The art could have ink, brushwork and paper, or use video, performance, sculpture, or other media; it may not even look like a traditional ink painting at all.’ It is this layering of past and present, of tradition and its constant transformation, that distinguishes contemporary Chinese art and provides much of its fascination for both Western and (increasingly) Chinese audiences.

In fact, it seems that ink itself is no longer necessary for a work to be defined as ‘contemporary ink painting’. The gesture or the mark is sufficient, even in the form of sculpture, video or photography. From Xu Bing’s re-interpretations of literati masterpieces using debris and rubbish behind backlit screens, to the digital multimedia works of Yang Yongliang, the ‘Family Series’ of Zhuang Huan, the gunpowder works of Cai Guo-Qiang, and the recent cartographic works of Qiu Zhijie, the label of ‘Contemporary Ink’ is being applied to the works of many artists who may themselves not always agree with the interpretation. The Wall Street Journal has identified contemporary ink painting as the ‘next big thing’. A major exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China opens in December 2013, and will include Xu Bing’s installation ‘A Book from the Sky’ (1989), and Ai Weiwei’s ‘Map of China’ (2006), which is constructed entirely of wood salvaged from demolished Qing dynasty temples. Sotheby’s and Christies have recently gone head to head with sales of contemporary ink works in Hong Kong.

Even the most casual observer of Chinese contemporary art cannot fail to notice the myriad ways in which Chinese artists are working within and reinterpreting these traditional forms. New interpretations of a ‘Shui Mo’ (ink and water) tradition pose a challenge the hegemony of oil painting, which has dominated the art world in China since the rise of the avant-garde painters in the early 1990s. One might take a cynical view and suggest that there is a great deal of marketing going on.

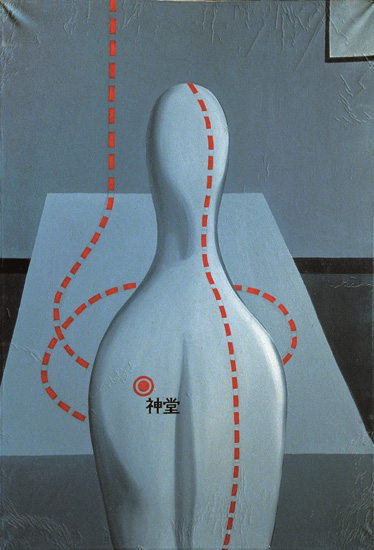

In the work of one Beijing artist, however, the tradition of brush and ink has become a way to express deeply personal, spiritual, cultural and even political concerns. Bingyi Huang(usually known simply as ‘Bingyi’) lives and works in a Yuan Dynasty temple building on the ancient central axis of Beijing, near the Drum and Bell Towers. The vast space of her studio, with its enormous pillars and antique furniture, orchids and birds fluttering in large cages, is a tranquil oasis. Once across the stone threshold and inside the heavy wooden doors the shouts of street vendors, and the honking horns of motorcycles and cars navigating the narrow laneways of the hutongs, seem very far away.

When I met Bingyi in October she had just returned from a period of some months painting in the mountains a few hours outside Beijing. Her assistants carefully unrolled a 30-meter long painting to show me how she has developed a unique approach, fusing ink painting with land art, installation art and even performance art. I ask her what she thinks about the current international interest in renewed traditions of ink painting, and she laughs, saying, ‘I could not care less.’ I am doubtful, asking again why she thinks western audiences are so intrigued by the contemporary interpretations of this ancient art form, but she says again, emphatically, 'I couldn’t care less about the art market, about auction prices, it’s boring. In my case it’s not about reinterpreting Chinese traditional ink painting. If you are truly ‘Shan Shui’ you don’t need to think about it. If you are the being, you don’t need to think about the being. You just are.’ She describes her work in an intensely spiritual manner, ‘It’s the universe working through me,’ she says, ‘and sometimes it’s that space between human hand and God’s hand.’

Becoming a practising artist only six years ago, after an extraordinarily diverse career, in which she switched from biomedical engineering to art history, along the way also studying computer programming, music and finance, she has created a painting idiom which she describes as a search for the sublime. This is not the European Romantic sublime of the human being as a passive observer of the power of nature, however, but rather a specifically Chinese notion informed by Buddhist beliefs and by her years of art historical research into the Han Dynasty. Bingyi completed her PhD at Yale in 2005. ‘I lived with the Han Dynasty for seven years,’ she says, ‘I was them!’ And what she learned from the years researching her dissertation was that through art, ‘one can embody the notion of eternity. If you can feel and express eternity and transience, then you are approaching a much higher level of metaphysics.’ She tells me that she began painting in her mother’s living room in 2006. ‘What drove you to become a practising artist after a successful academic career?’ I ask. ‘I always wanted to,’ she says. ‘What lies in the heart of humans is a desire to express. We all wish to express, but the question becomes “What is your embodiment? What is your medium?” It was completely inside of me, completely contained… One could say that it’s fate, but we Chinese have a different way of perceiving that.’

Her recent work, Journey to the Centre of the Earth, created for a site in Essen, Germany, a mining region of dramatic mountainous landscapes, is an ink painting of 150 metres in length – a length which equals the depth of the shaft of the first mine. It is developed from meticulous research. Weather, geology, geography, history and sociology are all elements that Bingyi investigates in the planning process for a project such as this. She began the research in Germany and then moved into the mountains outside Beijing for two months, camping in 45 degree heat, in order to physically create the work. Working with four assistants, she worked on the painting section by section, applying the ink to the paper with a variety of techniques and tools that would astonish the traditional literati painters. In an exhaustive and painstaking process her assistants even created a man-made pond large enough to make the sheets of paper that are joined end to end to create the vast scroll.

‘I was standing between the heaven and the earth,’ says Bingyi. Dealing with the extreme physical discomfort of the conditions, she says, and even finding herself covered with mosquito bites, was all an important element of her practice. ‘I could feel I was no different than a mosquito, I was no different than a toad. That’s eternity – you are so minimal, you are nothing. And that is the sublime.’ She explains that this process is entirely different than traditional notions of landscape art or Chinese ‘Shan Shui’ (water and mountain painting) in which the artist observing and recording nature. ‘Nature is just a projection of the universe.’ This is not landscape painting in either its western ‘sublime vista’ guise or the Chinese ‘Shui Mo’ (water ink) tradition. ‘It’s conceptual, it’s land art, it’s performance art,’ says the artist. ‘It’s a ritual I perform between Heaven and Earth. I am not a shaman, I am just a human, but this ritual is relational between the universe and the individual, it’s a kind of sublime. It’s intensely primal. It raises questions about our fundamental being – what is pain, what is suffering, what is loneliness.’

To read the rest of this article, click HERE