|

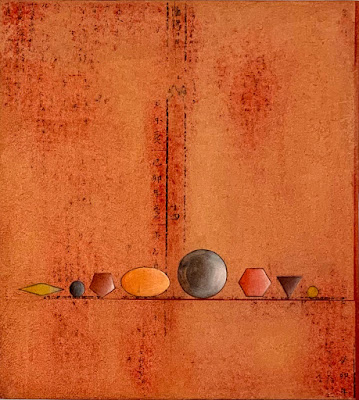

| Tony Scott, New Health Plan, 2007, image courtesy the artist |

In pre-pandemic days it was my habit at this weirdly liminal time to reflect on the year's experiences of exhibitions, visits to artists' studios and inspiring (or at least interesting or strange) encounters in the artworld. Needless to say, 2021 has been another year of living (with great trepidation) dangerously, thanks to Covid-19. It presented sadly few opportunities for encountering art or artists beyond the window of my computer screen.

Nevertheless, despite the pandemic, the lockdowns, and the general malaise, I have managed to meet and write about a number of interesting artists as well as (almost, almost, so close!) completing a PhD thesis. And teaching keen postgraduate students, most of whom were in their Chinese hometowns rather than studying in Sydney as they had hoped to do.

In a brief hiatus between lockdowns it was wonderful to actually see the Yang Yongliang exhibition at Sullivan & Strumpf for which I had written an essay, and to speak about his work to invited viewers in the gallery. Unable to travel to China, I have nonetheless continued to interview artists and publish articles, including my conversations with Charwei Tsai, Tianli Zu, Louise Zhang and Cindy Yuen-Zhe Chen in COBO SOCIAL and an essay for Cao Yu's solo show at Urs Meile Gallery Beijing (which you can read HERE). I had hoped to be able to travel to Norway in May 2022 for the opening of a major exhibition of women artists from China at Lillehammer Museum called 'Stepping Out'. I was honoured to be invited to join an academic reference group for this important project, and to write an essay for the catalogue, but it seems unlikely that I can be there for the opening. Maybe in 2023 when the exhibition travels to the Museum der Moderne in Salzburg...

One great pleasure in these dispiriting times was writing an essay for my dear friend Tony Scott's survey show at Glen Eira City Gallery. 'Back from China' reflected on an extraordinary life's journey from Melbourne to Beijing, to Hong Kong and back again. Thinking about Tony's work prompted memories of shared China adventures. It is due to Tony's generous spirit that I was able to meet wonderful artists such as Gao Ping, Hu Qinwu, Huang Xu and Dai Dandan on my first trip to China in 2010. Within hours of arriving in Beijing as a completely bamboozled first-timer (Beijing is ... a lot) I found myself eating dumplings with Tony, then attending a gallery opening in Caochangdi, and then joining an artist's dinner at famous Yunnan restaurant, Middle 8th, thinking to myself all the time, 'Dorothy, you're not in Kansas any more!'

|

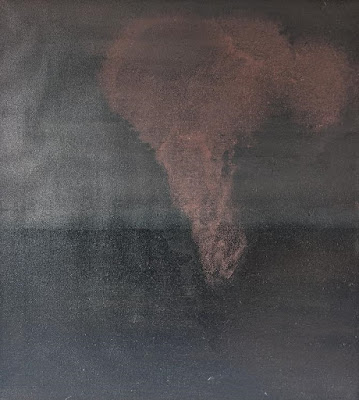

| Tony Scott, 1 Cloud in Gold Landscape, 2021 Chinese Paper, Oil Paint, Pigment on Canvas 35 cm x 45 cm, image courtesy the artist |

Other memories include Tony's residency in Chengdu in 2013, when he persuaded me to make a speech at the exhibition opening. I had arrived on a flight from Beijing (on Sichuan Air, where the flight attendants bring pots of chilli sauce up the aisle and ladle it onto your food) having no idea that this was going to happen. I wrote the speech on a borrowed laptop in about an hour and then joined a line-up of Party officials and the Australian consul general, where I was introduced as 'a famous art critic from Australia'. As my speech was translated into Chinese, line by excruciating line, I felt that my life was slipping away even as I spoke - it seemed to go on for hours. Writing the essay, then, was something of an exercise in nostalgia for China, and Tony's work is wonderful, so I share it here with his permission.

|

| Tony Scott, Shelter 1, 2019, Oil Paint, Almanac Pages on Board 24 x 22 cm, image courtesy the artist |

Cartographies of Memory: the work of Tony Scott

“I’ve

come back—return journeys

Always take longer than wrong turnings—

Longer than a lifetime …

Crossing the black map

Ushering you like a windstorm into flight …

I’ve come back—there are always

Fewer reunions than partings

But only by one.”

Excerpted from ‘Black Map’ by Bei Dao (2008), translated from the Chinese by Tao Naikan and Simon Patton

Mountain

peaks beneath big skies, sweeping storm clouds, and the shapes of traditional

‘scholar rocks’ are a constant presence in Tony Scott’s works, juxtaposed with

references to medicine, the body, and human frailty. These themes of human

beings in dynamic relationship with the natural world, cosmologies of an

interconnected universe, seem very Chinese. Unsurprisingly – Scott lived and

worked in China for many years. His body of work resembles a diary of outward journeys

and homecomings, a map of memory. Shaped by the artist’s long experience of a

country he first visited in 1994, the emphasis in his paintings, mixed media works,

and installations is on the importance of landscape, the visceral physicality

of paint, and the nostalgic associations embodied in objects found in Chinese

flea markets.

|

| Tony Scott. Silver Cloud 4, oil paint and pigment on joss paper, image courtesy the artist |

Although Scott now lives and works in Melbourne, painting in a suburban garden studio rather than in the ramshackle artist villages on the outskirts of Beijing, China is ever present in his work. Recurring images of mountains, clouds and human body parts evoke the Daoist/Confucian cosmology of tian di ren heyi, in which everything under heaven (tian) exists in a mutually reciprocal and interdependent relationship. In Daoist/Confucian and Buddhist belief, the mountains are the home of the Immortals, and the earth contains the ancestors.[i] Dramatic peaks wreathed in clouds were the favourite subjects of the literati shan shui (mountain and water) painters,[ii] and mountains beneath cloud-filled skies are a constant theme in Scott’s works too.

Scott

describes his first visit to China as intoxicating and transformative – he

worked on an exhibition installed in a pavilion in Beijing’s Temple of the Sun

Park (ritan gongyuan) and witnessed the city’s demolition and

reconstruction in an optimistic and relatively liberal time of dynamic change.

Like many first-time travellers to the Middle Kingdom, he was hooked. Returning

again and again over the next several years, Scott settled in Beijing in 2004,

where he lived until he moved to Hong Kong in 2013. In 2016, sensing the winds

of change that have now so dramatically altered Hong Kong, he made the

momentous decision to return to Australia. In his Melbourne studio Scott’s work

has taken on a new energy; he has been feverishly prolific. It is as if

imagery, colour, form, and painterly surfaces have been simmering and

strengthening since his homecoming.

Scott’s survey

exhibition reveals a consistently experimental, tactile, eclectic approach to

materials and to the expressive possibilities of paint applied to richly

layered surfaces. A close look often reveals glimpses of underlying,

Schwitters-like collage materials including gold or silver funerary joss

paper, Japanese wallpaper, and assorted paper ephemera collected on his

travels. These materials embody the artist’s investigation of his passage

through the world and through time. Installed together, Scott’s landscapes,

installations of found objects, and the occasional figurative painting make up

a multi-faceted autobiography.

A series of re-worked

painted heads, for example, suggests a shifting, fluid identity. Self

Portrait – Red (2000-2020) depicts the artist as a blank, featureless

silhouette, a tabula rasa to be over-written with new experiences. In Self

Portrait with a Pyramid (2000-2020) Scott represents himself as a yellow

outline. The hint of a face, or possibly a second presence, emerges through

scumbled layers of paint and glaze. Drips of pigment and solvent render it

evanescent, ghost-like. It suggests the layered, complex identity of the

transcultural traveller, a selfhood in a continual process of reconstruction. The

faint pyramid seen in this painting prefigures the later Shelter series

and also echoes the repeated forms of mountains that appear in so many works. Hints

of Scott’s earliest Chinese sojourns emerge here too; the grey tones evoke the

beautifully bare bones of northern Chinese winter landscapes and the grey

courtyard walls of Beijing’s traditional hutong neighbourhoods. A hint of red

appears through mist, evoking an urban landscape of grey air, grey walls, and red

courtyard doors.

Beijing is physically

present in installations utilising objects and materials found at the extraordinary

Panjiayuan ‘Dirt Market’, the source of treasures ranging from antiques (mostly

fake) to Chinese furniture, old letterpress blocks, books and paper ephemera, and

porcelain shards. It was Panjiayuan that provided wooden acupuncture figures –

dummies covered with tiny holes for the needles and marked with the ‘qi’

meridians of traditional Chinese medicine – for two major installations. In New

Health Plan (2006) the figure is connected with wires to instruments for

measuring electric current. Recalling Dr Frankenstein’s monster brought to life

with arcing jolts of electricity, this work was produced after the grim years

of the SARS epidemic and reflects on human frailty with wry humour. It seems

more than ever prescient now, as we wonder whether a ‘new health plan’ for

humanity will emerge from these last terrible years of a global pandemic.

Another work

featuring an acupuncture figure, Blood Pressure (2021), reveals Scott’s

fascination with the gruesome illustrations in ‘Gray’s Anatomy’. Flanked by anatomical

illustrations of human hearts beneath layers of paint, above the figure a gaudy

LED sign reads ‘high blood pressure’ in Chinese characters. The work confronts

us with the ephemeral nature of human existence. It also suggests a different,

non-physical ailment – the vulnerability and heartache of love. In a similar

vein, Measuring the Heart (2021) demonstrates Scott’s witty use of found

objects. Two slide rules are mounted on Chinese silk within a Chinese picture

frame, a neat bit of double coding that represents two kinds of crisis: the

stress test of the electrocardiogram, and the panicked moments of romantic

doubt and desire which most of us have experienced at one time or another.

|

| Tony Scott, Mooncake Balance, 2021, mooncake mould, brass plumb bobs, brass hangers |

Mooncake

Balance (2021) continues

this theme of measurement with brass plumb bob weights suspended beneath an

antique mooncake mould. It’s an elegantly minimalist juxtaposition of

apparently unrelated objects that plays with ideas about how things – and

people – are weighed and measured, literally and metaphorically. The moulds, of

course, are empty, and the plumb bobs establish a vertical line that leads

nowhere. There are art historical references here to Surrealist objects, to Man

Ray, and to Marcel Duchamp’s Dada ready-mades. Man Ray’s sly humour in works

such as Indestructible Object (1923, remade in 1933) – the famous

metronome to which he attached a photograph of an eye – or his Cadeau

(‘Gift’) of 1921 – an iron with a row of nails facing outwards down its centre

– are artistic ancestors of the wit Tony Scott brings to melancholy subjects. These

essentially obsolete objects have an absurd yet poetic presence; they possess a

significance beyond the logic of the everyday.

The constant

theme in Scott’s work, though, is the landscape – Australian and Chinese. These

ancient landscapes of rolling mountains, dry as a bone, are often painted over

found surfaces such as Chinese almanac pages, or funerary paper. While based in

Beijing, and later in Hong Kong, Scott travelled frequently between Chinese

cities, exhibiting in Shanghai, Chengdu and Xiamen. Many works depict sensuous

mountain forms and blurry glimpses of landscape as if seen from the window of a

fast train. Scott’s transcultural painterly idiom of space and form is

inflected by both Chinese and Western art histories. There is awareness, too, of

‘material art’ (caizhi yishu) practices whereby contemporary Chinese artists

use culturally encoded materials such as xuan paper, ink, silk, old books and

even tea and gunpowder.[iii]

Scott, moving between outsider/insider identities after so long in China, has

found his almanacs and printed books, and his ‘dirt market’ finds such as

mooncake moulds and acupuncture figures, to be evocative visual metaphors. They

are powerfully nostalgic, yet avoid any hint of slick Chinoiserie, a difficult

feat for an artist working between eastern and western cultures, but one that

Scott navigates adroitly.

40 Days

in Xiamen 1 and 2 (2019),

for example, are installed as panels resembling vertical scrolls, supported by

mooncake moulds serving as plinths. Soft tones of warm red in subtle washes painted

over Chinese almanac pages create the illusion of distance, revealing the

influence of literati shan shui ink painters and their nuanced

gradations of every possible shade of ink wash. Almanac pages emerging from

beneath layers of pigment suggest a narrative of the artist measuring out time

on his visits to the coastal city. We are left to imagine what happened in

Xiamen, but the vertical drips of paint create a melancholy sense of loss.

On the Li

River (2020), is

painted over acupuncture manual pages. The dramatic forms of southern China’s

karst mountain landscapes, so beloved of Song Dynasty shan shui masters,

emerge through richly scumbled layers of oil paint, pigment and wax, like an

almost forgotten record of a voyage long ago. In By The Great Wall 1 and

2 (2021), painted on Chinese joss paper on aluminium, Scott evokes the

bleak beauty of the mountains north of Beijing. In winter this landscape seems

an unrelieved vista of grey – the ancient grey wall against grey earth and grey

sky – yet in spring it is transformed to a sea of pinks and mauves with

blossoming trees.

|

| Tony Scott, Dust 1, 2021 Acrylic, Oil Paint, Pigment on Canvas image courtesy the artist |

Often, as

with the Storm Approaching series, there is a sense of foreboding

in these paintings. White clouds partially conceal mysterious calligraphic

marks that hover over the mountain range below or resemble sinuous river

systems seen from above. In the Geometric Landscape and Dust series

we can almost smell and taste the brown dust from the Gobi Desert that so often

blankets Beijing. Dust 2 (2021), for instance, hints at Scott’s earlier,

quite formalist, abstract visual language based on a Mondrian-like grid. It

evokes the repeated architectural forms and map of Beijing’s streetscape,

designed on an axis of the four compass points that symbolised the emperor’s

‘mandate of heaven’. Divided into unequal vertical halves and bisected by a red

horizontal, Dust 2 is a minimalist poem of deep burgundy, maroon and

dusty pink, overpainted and scraped back like the weathered surface of a hutong

wall.

|

| Tony Scott, Silver Cloud 1, 2021, oil paint and pigment on Chinese paper, image courtesy the artist |

Clouds are

ever present in these paintings, floating above the kind of mountain scenery in

which you might expect to see a lonely monk or scholar contemplating nature in

a literati ink painting. Five Mountains 1 (2020) is luminous in shades

of magenta, orange and red, with lyrically gestural clouds floating in the

heavens above. Three Black Mountains (2021), in contrast, is the most

foreboding of Scott’s mountain landscapes; layers of acrylic, oil paint, and

wax on paper are scraped, scored and sgraffitoed with mysterious markings. A

sliver of light over the humped forms of mountains beneath heavy clouds lit by

flashes of lightning suggests the unpredictable power of nature.

|

| Tony Scott, Flying Home 3, 2020, Collage, Oil Paint, Pigment on Board, 20 cm x 20 cm |

Scott’s painterly mountains have recently metamorphosed with the addition of 3-D printed mountain forms arranged on shelves in front of paintings under glass domes, or on petri dishes. It is as if they have been brought into being through some alchemical experiment. These forms in turn relate to a series depicting rocks arrayed in a landscape. They reference the Chinese fondness for the ‘scholar rocks’ (gongshi) whose twisted, fantastical forms are found in every Chinese park and formal garden. Pitted and perforated – either by natural forces of water, wind and weather, or artificially enhanced to be more aesthetically appealing – they were admired from the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE). Believed to symbolise the mountain peaks inhabited by the Immortals, representing the transformational, mutually reciprocal relationships between yin and yang in Daoist cosmology, they were collected by connoisseurs, displayed in gardens, and painted by artists. Small, ornamental versions were prized objects in a scholar’s study. In Scott’s works they are somewhat ambiguous, sometimes taking the form of human organs. In 13 Rocks on a Horizon (2021) they are painted over ‘Gray’s Anatomy’ illustrations of veinous eyeballs and other body parts, becoming a hybrid mountain range in which human and the natural world are one, beneath an ominous sky. Floating (2021) depicts a row of scholar rocks that have become detached from the earth and hover weightlessly in an amorphous grey space, suggesting the Daoist non-action, or effortless harmony, called wu wei.

|

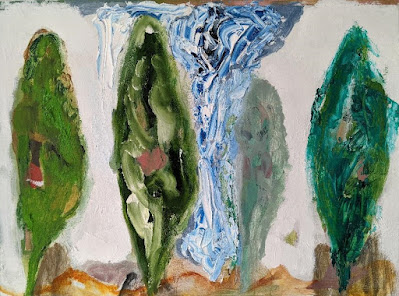

| Tony Scott, Gardening in Caulfield 4, 2021, Collage, Oil Paint on Paper

28 cm x 35 cm image courtesy the artist |

After so many years of navigating the often-labyrinthine, even Kafka-esque, Chinese art ecology – not to mention negotiating the exhausting pace of day-to-day living in a city like Beijing – is it possible that Scott has found peace at home in Melbourne, painting in his garden studio? Looking at the Gardening in Caulfield series it would seem so: in Gardening in Caulfield 5 (2021), painted on Japanese wallpaper, the familiar forms of scholar rocks and mountains appear to recede into a misty distance while rich earth and burgeoning plant forms occupy the foreground. Gardening in Caulfield with Trellis (2021) reveals a row of cypress or pine trees emerging from darkness. A suburban garden trellis replaces the Great Wall of China. A curved form of purplish soil resembles the mountain ranges of earlier works, suggesting the slow turning of the earth on its orbit around the sun and the rhythms of a human life. It’s a smaller landscape, a peaceful and domestic space. Yet in Scott’s richly layered paintings it is as eventful and filled with energy as those he remembers from China.

“I’ve come back—there are always

Fewer reunions than partings

But only by one.”

Tony Scott, Gardening in Caulfield 5, 2021

Japanese Wallpaper, Oil Paint on Canvas Board

40 cm x 30 cm, image courtesy the artist

[i] Tian di ren heyi or tian ren heyi (天人合一) refers to the unity between humanity and

the natural world.

[ii] Shan Shui (山水), literally translated,

means ‘mountain and water’, and refers to imagery of landscape in Chinese ink

painting.

[iii] Art historian Wu Hung’s theory of the significance of

materiality in the work of Chinese contemporary artists underpinned his

curation of ‘Allure: The Art of Matter’ shown at the Smart Museum of Art, University

of Chicago, in 2019. Examples of this ‘material’ approach include Liang

Shaoji’s installations featuring the thread-like filaments wound by silkworms;

Cai Guo-Qiang’s use of gunpowder; Wang Lei’s use of old books; Xu Bing’s giant

phoenixes made with building site debris; Zhu Jinshi’s enormous installations

made from xuan paper, and Gu Wenda’s use of human hair. There is a

relationship between the cultural meanings embodied in these works and Scott’s

use of Chinese found materials such as acupuncture figures.