I wrote this piece for Daily Serving after my experience of two dramatically different exhibitions in Beijing. Firstly, Zhang Xiaotao at Pekin Fine Arts - work which was technically extraordinary, skilful and refined, highly engaging and accessible on many levels - and emanating from a sincere engagement by the artist with important ideas. (Although. when my husband read my earlier interview with Zhang he said, "Hmmm. He seems to have some curious ideas about what quantum physics is.") The second exhibition seemed to me cynical and derivative - and deeply disappointing. Here's an extract from my review:

There has been noise of late about the supposedly derivative nature of contemporary art, about questionable curatorial practices, and about the piratical behavior of the art market. “Zombie Formalism” and “Crapstraction” are glib, voguish—although, it must be said, amusing—terms that have been thrown around. Whatever you may think about this critique of current tendencies in abstract painting, it seems that all is not well in the world of contemporary practice. There is a growing sense that contemporary art has entered a swirling vortex of derivative quotations from the past—a Mannerist phase, perhaps. But is any of this relevant to contemporary art practices in China? After a disappointing exhibition across three major Beijing galleries, Zhang Xiaotao’s solo show at Pékin Fine Arts makes me believe that art still matters.

Zhang Xiaotao believes that artists are "like alchemists"

For the last few years, in regular visits to Beijing, I have been delighted to encounter work that seems to have escaped the dead hand of suffocating theory. Certainly Beijing has seen its share of the “art as spectacle” phenomenon, with artists tempted by the accessibility of large spaces, cheap labor, and cheaper fabrication costs to make works that are bigger and shinier than they need to be. But that’s the world we are living in now—a world of giant rubber ducks everywhere and butt-plug sculptures in the center of Paris. Art as entertainment. An evaluation of 2014 exhibitions in a Sydney newspaper pointed out that these days “you can’t just put stuff on the wall and expect that lots of people will come see.” People expect something momentous, something extraordinary; they want their perceptions altered. In short, they want art to be magic.

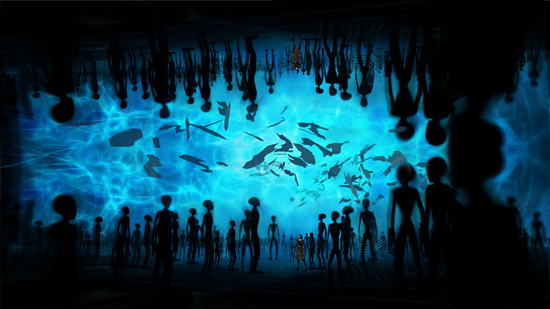

And, sometimes, just sometimes, it is. My most enduring memories of the all-too-rare transcendent art experience include Cai Guo-Qiang in Brisbane, Xu Bing’s magnificent Phoenix in New York, and Huang Yong Pingat Beijing’s Red Brick Art Museum. Which is not to say that I haven’t also seen some wonderful painting, most particularly in Beijing and Shanghai. No “Zombie Formalism” there. To my list of the extraordinary I can now add Zhang Xiaotao’s digital 3D animations at Pékin Fine Arts, in his solo exhibition In the Realm of Microcosmic. Two works, Sakya (2010–2011) and The Adventures of Liang Liang (2012–2013), were exhibited in the 55th Venice Biennale, in the China National Pavilion’s Transfiguration curated by Wang Chunchen...Read more HERE

And now its polar opposite, an exhibition that made me wonder what on earth I was doing teaching and writing about contemporary art in the first place...

A major event on the Beijing calendar each year at Pace Beijing has been Beijing Voice, which showcases current discourses and directions in contemporary Chinese art. This iteration, the fifth, was curated by artists Sun Yuan and Peng Yu with independent curator Cui Cancan. For their project Unlived By What Is Seen, they had 2,000 square meters of exhibition space to play with in Pace Beijing alone, as well as two other major Beijing galleries—Galleria Continua and Tang Contemporary Art. The curators selected twenty-eight artists and three artist collectives to participate in an exhibition intended to interrogate relationships between the artist, the art object, and the audience.

They present works in support of a theoretical position: that there is a shift in focus from making art to taking action; a move away from the production of images and objects. Instead, the artists are “developing modes of existence that interrogate life itself,” according to the somewhat opaque publicity material. In many instances the result of this is an artist-as-talking-head narrating personal stories or aspects of daily life to a video camera. Unsurprisingly, some of these are much more interesting than others. The documentation of performance works offered little that seems new. Sun Yuan volunteered to allow the artist Zhao Zhao to stab him once in the back with a knife. I think we may have seen this once or twice before.....

Young artists have always questioned the nature and purpose of art—where would the 20th century avant-garde have been without that? While there is no doubting the sincerity of the curators, or the artists, in their belief that they are challenging the hegemony of the art market and what they deem “ossified modes of making art,” by the time I left the last of the three galleries I was beginning to feel that Joseph Beuys has a lot to answer for. For me, at least, the base metals had not turned into gold.

And read the rest of the article HERE