|

| French Concession Shanghai, photo LG |

After 7 action-packed days in Shanghai I have arrived in Beijing - as always struck anew by the stark differences between these southern and northern cities. Reflecting on my week interviewing artists in Shanghai, my impression that the Shanghai artworld is growing ever stronger, and more interesting, is reinforced. The influence of the new private museums, the Yuz and Long Museums, now a major force to be reckoned with, is a significant factor.

|

| Bicycle Repairs, Shanghai, Photo LG |

My hotel in Shanghai's former French Concession was in a fabulous location for exploring the city on foot, and for navigating the Metro - wonderfully efficient, although not for the faint of heart during the rush hour. It was, however, of a uniquely Chinese type - on the surface very luxe, with glittery lamps, lots of fairly appalling art (for sale), enormous marble bathroom and pseudo-antique Chinoiserie. The room, however, was pitch dark even with all the lights on and the curtains open, the carpets in the corridors were badly stained and often covered with drop-sheets (Why? Who knows!) and the breakfast was beyond appalling - once tried never repeated, which perhaps is their intention. However, as Chinese hotels go, it all ran pretty smoothly.

My most memorable Chinese hotel experience was in Beijing, in the winter of 2012, at a supposedly swanky "art hotel" (now closed, and no wonder!) I had begun to think I was the only guest, when on my second night at about 11.00pm there was an almighty noise of thundering feet and shouting in the corridor, and then a loud banging on my door. Imagine my astonishment when I looked through the peephole to find a young Chinese man, stark naked, beating the door with both fists. Later, safely home again, I told a gay friend this story and he said, "Give me the name of this hotel immediately!" I, however, was a little alarmed. I called the reception fuwuyuan, who said with apparent resignation, "Oh Miss, what we can do? He drink too much!" I suggested that perhaps in fact they they did need to do something, anything, anything at all! whereupon the manager rang back and told me they would move me to another floor. There was nothing to be done about Mr Naked Guy. Reluctantly I agreed, and waited for the manager to accompany me. He knocked on the door, I opened it, and together we stepped over the naked body of the man who was now completely comatose, lying stretched out across my doorway. The incident was never mentioned again for the rest of my stay. (Except when I told my translator, who refused point blank to believe that it could possibly have been a Chinese man - he told me I must be mistaken, as only a "waiguoren", a foreigner, would behave so badly.)

A more ludicrous (and less amusing) Chinese hotel experience happened in Xi'an, where I sent some clothes to the laundry and then waited for their return. And waited. When I rang reception they were most apologetic and concerned. A farce ensued, where I received knock after knock on my door, with staff from the laundry bearing ever more preposterous items of clothing and attempting to persuade me they were mine: mens' leather jackets, assorted tiny dresses for tiny Chinese ladies, and enormous jeans for enormous men. It culminated around midnight, with a staff member who simply could not accept that a sequin-covered blue suit (think Xi Jinping's wife on a state occasion) was not in fact mine. He became argumentative and kept trying to shove it at me through the door, which I eventually closed in his face. I never did get my best David Jones blue sweater back.

And of course, there are the two most bizarre experiences of all: the "Art Hotel'' in Chengdu where I discovered to my surprise - and horror - that I was expected to make a speech at the opening of an exhibition of an Australian and Sichuan artist. With about two hours to write it and have it translated, and with no fancy clothes in my overnight bag (perhaps I should have taken that sparkly suit after all!) I fronted up and discovered that my speech was to follow the local Party chiefs, the Chengdu Art Academy bigwigs, and the Australian Ambassador. I was introduced as a "famous Australian art critic" (ha!) and began in Chinese with an apology for my poor language skills. The artist's son then translated my speech line by line. I began to see my entire life flashing before my eyes as time seemed to stop and then go backwards. Dripping with sweat, I ploughed gamely on, filmed by three local television stations - thank God nobody is ever likely to see that footage.

But the honours for first place must go to the "Vineyard"- and I use those inverted commas advisedly - about two hours out of Xi'an, where I was taken to see an artist's work. My lunch with the artist, a property developer, and a returned Chinese movie producer from Hollywood is a story for another time. I will just say that the wine, the wisteria and even the fields of grapes stretching into the distance are all fake. The local farmers have been persuaded to stop growing corn and vegetables and instead grow table grapes so that wealthy city people can come on weekends and go grape picking and stay in the "chateaux". Truly a Marie-Antoinette at Le Petit Trianon experience.

|

| Yang Fudong, still from video at Yuz Museum |

But back to Shanghai, and to art! On my first visit to Shanghai, back at the start of 2011, a number of artists told me they felt almost like the poor relatives of their peers in the art centres of Beijing. Now, they talk about their independence from Beijing, their capacity to innovate and the ways that each individual artist can pursue a unique vision. One said that in his opinion Beijing artists indulge in way too much "liao tianr" - too much chat and communal thinking. I am quite sure, of course, that artists in Beijing will tell me an entirely different story! However, the fact remains that with a unique history of European Modernist influence, and a sense that Shanghai is a truly global city, artists here work in distinct ways. I was fascinated to be shown the extraordinary studio of Xu Zhen - the 'MadeIn Corporation' - where with the assistance of 40 artists/collaborators/assistants some incredibly ambitious and monumental projects take shape. Some say, with a bit of a sneer, it's merely "art as spectacle". I say, "Bring it on!"

|

| Xu Zhen, Guanyin and 'Shanghart Art Supermarket' at Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, 2014, Photo LG |

The massive Xu Zhen retrospective at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing last year was one of the most exciting exhibitions I had seen in years, from his enormous fluoro-coloured Guanyin to the Shanghart Art "Supermarket" where all the packaging is empty, and "grannies" shuffled around in slippers, following you through the aisles. "Eternity", a sculpture for which 3D printing technology created absolutely accurate moulds for casting the replicas of figures from Greek classical sculpture and ancient Chinese Buddha figures, is currently showing at White Rabbit Gallery in Sydney. The artist agrees, without apparent irony, that he is the successor to Andy Warhol and his "factory". He says, "Andy Warhol made a connection between art and commerce, but we recognise that art IS commerce and we aim to make the commercial, artistic." There is a similarly cool Warholian demeanour evident in conversation with this artist, who turned himself, literally, into a brand, recognising the global reach of the art market. At the same time, Xu Zhen supports young emerging artists with the MadeIn Gallery in Shanghai's M50 art district.

|

| Xu Zhen Éternity' at Ullens Center for Contemporary Art Beijing 2014 |

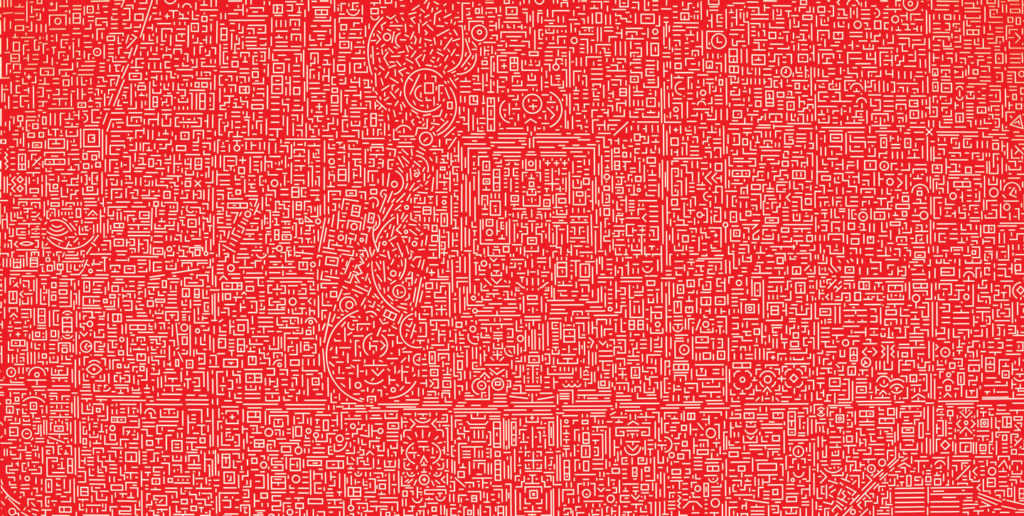

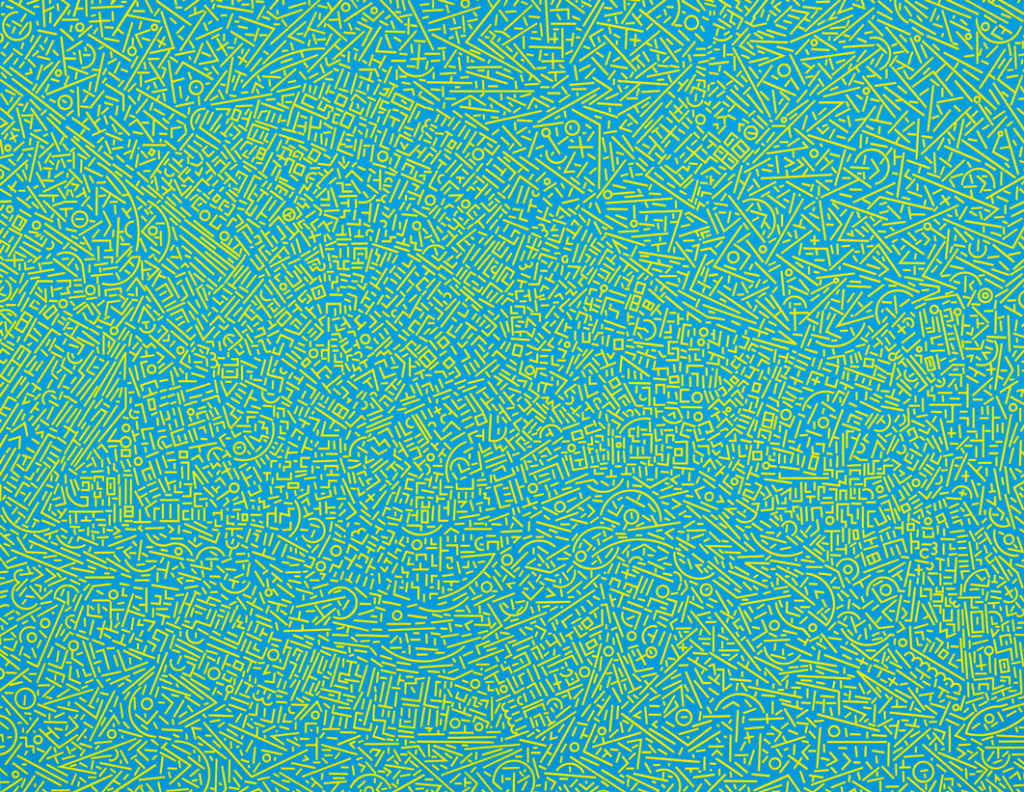

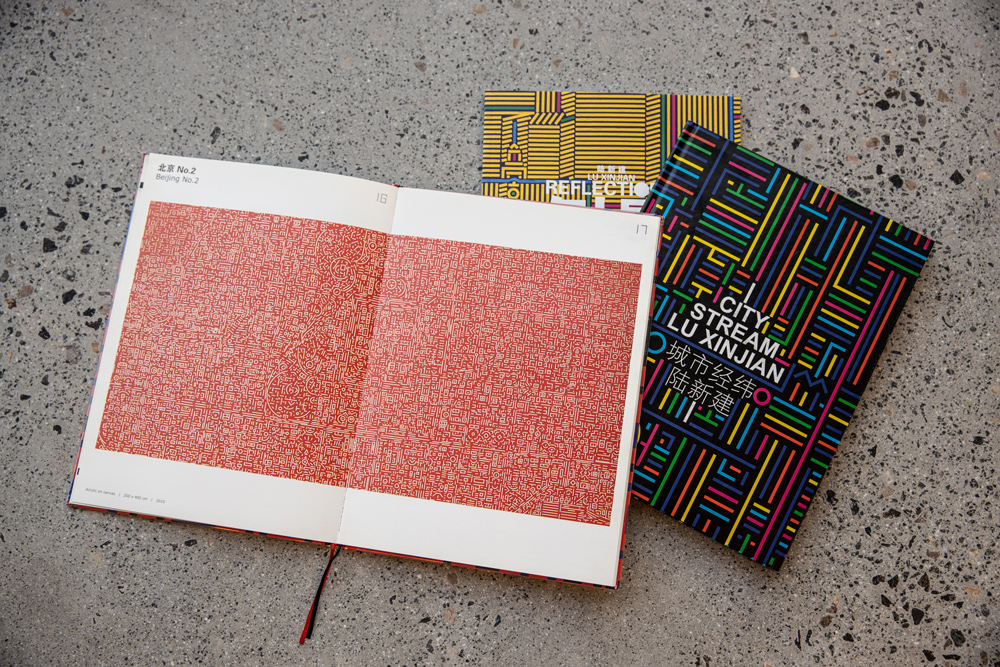

Artists such as Yang Yongliang, Chen Hangfeng, Lu Xinjian and Hu Jieming reinvent and recontextualise Chinese tradition and history in different ways, both subtle and overt. From papercutting to "Shui Mo" ink painting, from Gongbi realism to the revolutionary photography of the 20th century, each is taking elements of the past and making work that is absolutely contemporary and reflecting the realities of our world today. Chen Hangfeng is working on a significant project about the notorious village in southern China where most of the world's Christmas ornaments are made, an industry which has filled its waterways with glitter, tinsel and assorted festive crap. It's a village of great historical importance in China, in a most beautiful landscape where significant poems were written. Chen Hangfeng's work is a metaphor for globalisation, a theme which concerns many of these artists. Yang Yongliang continues to make beautiful digital works, and now also narrative films, relating to the destruction of the environment as Chinese megacities eat the countryside, devouring tradition in their wake. He takes thousands of photographs for each digital animation, often choosing to shoot in Chongqing. And no wonder - the greater municipality of Chongqing is now, by all accounts, the largest city in the world. Lu Xinjian continues his ''City DNA" and "City Streaming" series of paintings, inspired by aerial views, Google Maps and Mondrian. And Hu Jieming has begun several new projects, including one for which he has written computer coding that can take a photograph and reproduce it, making subtle and not-so-subtle alterations. From this he makes a painting, then scans it and repeats the process, over and over again. Each painting is further from the original image, more abstract. He is asking questions about the relationship between human observation and artificial intelligence.

|

| With Lu XInjian in front of one of his "City DNA" series |

After seven intense conversations with seven artists, a Saturday morning walk around the former French Concession provided breathing space, and time to re-acquaint myself with the idiosyncracies of Shanghai life, from the wearing of pyjamas as streetwear to the washing hanging on every street corner, and from powerlines and railings: "Shanghai flags." The sun shone, the oppressive humidity vanished, good coffee was readily available, the trees were green and beautiful, and life seemed very good. Visits to exhibitions at as many galleries as I could cram into one day, including Chen Zhen at Rockbund Museum, Yang Fudong at Yuz Museum, and an exhibition of work by women artists at Pearl Lam, provided a visual feast.

|

| Chen Zhen Purification Room, 2000 - 2015, found objects, clay, photo LG |

|

| Chen Zhen, Crystal Landscape of Inner Body, 2000, crystal, iron, glass, photo LG |

|

| Yang Fudong, still from video work, Yuz Museum |

|

| Lin Ran "Lesbos Island" - traditional Chinese medicine cabinet with drawers "filled with gifts and mementoes given to the artist by lesbians" at Pearl Lam Gallery Shanghai photo LG |

My Shanghai experience concluded with the Zhou Fan exhibition at Art Labor Gallery - beautiful works that appear marbled, or as if pigment has been gently dripped onto the surface with an eye dropper. The artist told me that every nuanced gradation of colour and finest line has been carefully applied with tiny brushes. Zhou Fan's practice exemplifies the subtlety and thoughtful refinement that co-exists with the chaotic frenzy of life in modern China.

|

| Zhou Fan, Mountain #0003, 2014, Acrylic ink and mineral color on paper, 38.3 x 56.7 cm image courtesy the artist and Art Labor Gallery |