|

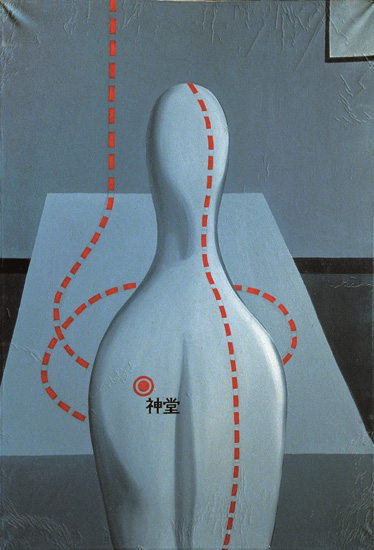

| Guan Wei, Apparition, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 10 panels, 180x254 cm. Image courtesy Vermilion Art |

Out of

the Ordinary is the

title of Guan Wei’s solo exhibition at Sydney’s Vermilion Art, a description that

also fits the man himself. From his early years in Beijing’s post-Cultural

Revolution contemporary art scene, to his arrival in Hobart in 1989 and

emergence as the most prominent of the so-called ‘post-Tiananmen’ generation of

Chinese artists in Australia, Guan Wei developed an art practice that merges

two worlds. His visual language as painter, ceramicist and sculptor juxtaposes

Chinese traditional motifs with Australian colonial imagery, and with continuing

references to the indigenous history that intrigued him from his earliest days

in Tasmania. The result is a surreal parallel universe, a place of imagined,

alternative histories.

Covering twelve

years of the artist’s work, Out of the Ordinary is a collaboration

between Guan Wei’s long-time

gallery, Martin Browne Fine Art, and Vermilion Art, Sydney’s only commercial

gallery specialising in contemporary Chinese art. It reveals distinct phases in

his practice over that time, and a variety of influences ranging from his

fascination with Australian beach culture to appropriations of the Chinoiserie

that was so fashionable in Britain and Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth

centuries. Prevented from

returning to his Beijing studio for three years due to Covid-19 border closures,

Guan Wei’s recent work examines the global pandemic as a kind of spiritual

malaise. We humans may need an extra-terrestrial intervention, he suggests,

whether that be from angels or aliens.

Guan Wei

once said that he likes to work in ‘the space between imagination and reality’:

he is a storyteller, a myth-maker – an artist with a strong sense of social

justice and moral conviction. His blend of real and imaginary histories creates

a world in which his characteristically faceless, pale figures interact

with silhouettes of animals and people that resemble paper-cuts. His paintings

are populated by Indigenous Australian, European and Chinese characters who wander in exotic landscapes or sail across painted oceans. Described poetically by

Alex Burchmore as ‘adrift in dense spaces of iconographic collision’[i],

Guan Wei’s eclectic imagery suggests stories of empire, invasion, exploration, and

migration – and often evokes a

contemporary political paranoia over ‘sovereign borders’. Together with his

distinctive iconography of Chinese clouds, swirling waves, map coordinates, navigational charts, and astrological diagrams they

create a floating world of ambiguous transnational narratives.

|

| Guan Wei, Play on the Beach No.2, 2010, acrylic on canvas, diptych, 130x106 cm. Image courtesy Vermilion Art |

The earliest

work in the exhibition, Play on the Beach 2, dates from 2010. Part of a series created on Guan Wei’s return from

China in 2008, the diptych suggests the simple, hedonistic Australian pleasures

of sun and surf, with curly Chinese clouds floating above a blue ocean. Yet

there is a hint of something darker. In the foreground, an emu

buries its head in the sand while a fleshy pink figure runs towards the ocean,

arms outstretched and mouth agape. In the background, tiny figures appear at

first glance to be frolicking happily in the ocean. On closer inspection,

however, we wonder whether perhaps they are not waving, but drowning.

Notions of

navigation – the crossing of oceans, the art of the cartographer, the study of

constellations – are significant in Guan Wei’s work. The exhibition features paintings

from two important series, Reflections and Time Tunnel, that were

inspired by a residency in England. Guan visited stately homes and historical museums

and became fascinated by the exploits of the British navy in the eighteenth

century. He studied maps and historical engravings and was inspired by

collections of textiles and porcelain with the Chinoiserie motifs so beloved of

the period. Contrasting a Rousseau-esque ideal of a Utopia in the Pacific with

the horrors of a brutal penal colony and the violence of the Frontier Wars,

Guan Wei developed new imagery to re-imagine these histories. He reflects on

the universal theme of the journey, on specific historical voyages, and on his

own journeys of migration and return.

|

| Guan Wei, Reflection 12, 2016, acrylic on canvas, triptych, 130x162 cm. Image courtesy Vermilion Art |

When the series was first exhibited Guan Wei described them as ‘floating between true and false, dark and light’. Reflection 12 (2016), for example, depicts what at first seems a bucolic idyll. In the blue tones typical of export porcelain or toile textiles, enclosed in an ornate frame, the foreground shows the silhouette of a woman and child feeding chickens. Cows and sheep stand in a small stream that runs beneath a curved stone bridge. A silhouetted figure playing a pipe recalls Arcadian landscapes by Watteau. In the background, indigenous figures are strongly reminiscent of the paintings of early nineteenth-century Tasmanian artist John Glover, no doubt encountered during Guan Wei’s time in Hobart. Glover’s paintings of Aboriginal ceremonies ignored inconvenient truths, presenting instead of dispossession and disease an imagined pastoral ideal of coexistence. In Reflection 12 the faint image of a sailing ship in the background, and the black silhouettes of an angel fighting a demon outside the framed landscape, allude to darker truths of our history. A four-panelled folding screen, Remarkable World 3 (2019) continues this interest in the intersections between colonial European, Chinese and indigenous histories, filtered through the artist’s imagination.

The most recent painting in Out of the Ordinary is The Apparition (2023), an ambitious ten-panelled contemporary version of a medieval altarpiece that distils Guan Wei’s response to the ruptures of the global pandemic. The lower five panels depict an ocean dotted with islands. The island peaks and swirling waves recall the mountain and water imagery of shan shui ink painting. Yet here, rather than lonely scholars or Immortals wandering in the mountains we see the biblical story of Noah’s Ark (with an abandoned panda looking on plaintively from the waves). Dinosaurs coexist with Chinese dragons and dolphins, and the sea is filled with capsizing boatloads of anguished human figures. Above, angels appropriated from Renaissance paintings appear to offer hope and salvation. Guan Wei says, ‘A terrifying flood submerged the world. People were struggling in the water. Noah's Ark appeared from afar and magical forces descended from the sky. Human beings who had been troubled by the pandemic for three years were, at long last, rescued. There is always hope.’ Yet, the tiny silhouettes of a submarine and hovering UFOs suggest that humanity is not out of the woods just yet. Guan Wei’s work always balances despair with hope, tragedy with humour, and the ordinary with the mystical.

Out of

the Ordinary

continues at Vermilion Art until 23 March 2023

[i]

Alex Burchmore, ‘Guan Wei’s “Australerie” ceramics and the binary bind of

identity politics’. Index Journal issue no. 4 https://index-journal.org/issues/identity/guan-wei-australerie-ceramics-and-the-binary-bind-of-identity-politics-by-alex-burchmore

,+2013,+oil+on+canvas,+121+x+160.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)