It's the end of 2013, another year over and a time to look back. Every writer of every description is doing their end of year roundups (aka "quick, make a list, rather than actually write something of substance") and "who am I to disagree?" to quote Annie Lennox and the Eurythmics. And that's always appropriate. Returned from a Chinese winter, exposing my startlingly white skin to the Australian sun and walking along the beach, instead of more practical and useful tasks I have been deciding on my top ten gallery experiences of the past year. I could have been thinking about New Year's resolutions such as, oh, I don't know, losing 10 kilos, going to the gym more often (or, in actual fact, ever), doing intensive Chinese homework every single week, being kinder and less impatient, being less of a workaholic. But instead, I decided to write a list of the aforesaid gallery moments of wonder and awe. And here they are:

1. Song Dong, Waste Not, at Carriageworks, Sydney, January 2013. This was magical and moving, a testament to family, to memory, a profoundly human elegy to the artist's mother and to times past.

|

| Song Dong, Waste Not, photographs Luise Guest |

When I wrote about this installation, which I had always wanted to see, I found it hard to express my own feelings of sadness that linked me directly with my own very complex relationship with my mother. Here is the start of my review for 'The Art Life'.

The Ancestral Temple: memory and mourning in the work of Song Dong

Ten thousand objects collected by the artist

Song Dong’s mother

Zhao Xiangyuan, over the course of her adult life, are arranged in neat rows and grids on the ground at

Carriageworks. During the Cultural Revolution, a period of extreme uncertainty and privation, she began hoarding – drying out and keeping even her allocated bars of soap for fear of future soap shortages. Continuing right through to her last years, Zhao saved everything, in a process called “wu jin qi yong”, translated as “waste not”. This is the latest incarnation of Chinese artist Song Dong’s extraordinary installation, itself entitled ‘Waste Not’.

Song Dong: Waste Not (detail, installation view) Photograph by: Jane Hobson Courtesy Barbican Art Gallery.

Entering the vast space one first sees a row of old chairs, and beyond them the reconstructed frame of Zhao’s traditional timber home. Radiating from the skeleton of the house, the possessions it once contained are laid out on the floor: among them 4 TVs, 3 record player turntables, numerous clocks and watches, broken toys, lamps, old umbrellas, plastic buckets and tin washing tubs, rows of shoes, coat hangers, threadbare face washers, stacked quilts and blankets, polystyrene food containers, empty plastic bottles and their lids, and hundreds of plastic bags folded into neat triangles. They are unbearably poignant in their sheer ordinariness. To read the rest of my review in The Art Life, click on this link:

theartlife.com.au/2013/the-ancestral-temple-memory-and-mourning-in-the-work-of-song-dong/

2. Liu Zhuoquan, Chang'An Avenue, at Sydney Contemporary, August 2013

.jpg) |

| Liu Zhuoquan. Chang'An Avenue (detail) image courtesy the artist and China Art Projects |

I have loved the 'neihua', or 'inside bottle painting' installations of this artist from my first encounter with him at his Beijing studio early in 2011. A major installation at the MCA for the 18th Biennale of Sydney in 2012 gave Sydney audiences a sense of his ambition and range. His recent work, shown here for the first time at the Niagara Galleries booth at the inaugural Sydney Contemporary Art Fair, is an indication of the way his practice is continuing to develop.

3. 'Serve the People', curated by Edmund Capon at White Rabbit Gallery, Sydney, August 2013

Each show at the White Rabbit Gallery of Contemporary Chinese art presents us with intriguing new works as well as old favourites in new juxtapositions. Edmund Capon, retired (liberated?) from his role as Director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, curated this show and it was excellent. Even the gallery spaces themselves looked different and the works were selected and arranged to elucidate his narrative, which related very strongly to his own memories of China during the Cultural Revolution. And why read John McDonald's review if you can read mine?

|

| Jin Feng, History of China's Modernisation, Volumes I and II, 2011, rubber, marble, ricepaper installation, image courtesy White Rabbit Gallery |

.jpg) |

| Shen Shaomin, Laboratory - Three-Headed, Six-Armed Superhuman, 2005, bone, bone meal, glass, glue, dimensions variable, image courtesy White Rabbit Gallery |

|

| Chen Wenling, Happy Life - Family, bronze with vehicle duco, 2005, (with Gonkar Gyatso Buddha at rear), image courtesy White Rabbit Gallery |

Here is the start of my review for The Art Life:

Serve The People

Wang Zhiyuan ‘Object of Desire’, 2008, fibreglass, lights, sound, 363 x 355 x 70 cm image courtesy the artist and White Rabbit Gallery

In Mao Zedong’s famous exhortation to the Red Army at the 1942 Yenan Forum on Art and Literature, he emphasised the close relationship between art and revolution, stressing that art must ‘serve the masses’. He probably wasn’t envisaging a gigantic pair of gaudy pink knickers made of fibreglass and car duco; a three-headed conjoined baby skeleton in a scientific bell jar; vegetables growing in an illicit Shanghai garden engaged in a sexually explicit conversation courtesy of Chen Hangfeng’s video installation; or a baby stroller customised with spikes on the wheels, symbolising the fierce struggle for success that characterises parenthood in today’s China. Imagine the bewilderment of Mao and his revolutionary comrades in an encounter with these works and others in the new exhibition at White Rabbit Gallery. ‘Serve the People’ has been curated by former director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Edmund Capon, from Judith Neilson’s impressive collection of contemporary Chinese art.

The notion of how art might “serve the people” has an entirely different resonance in today’s China. Artists born before Mao’s death in 1976 cannot help but look back and attempt to reconcile their life experience with the strangeness of the present day. The dislocations of social transformation, globalisation, demolition and urbanisation which have swept away the revolutionary past, ushering in a world filled with uncertainty, have rendered many of the tropes of the first 1990s wave of contemporary Chinese art passé. A new visual language is emerging, with which artists can respond to the strangeness of their contemporary world, in which enormous disparities of wealth, education and personal freedom are creating new schisms in the social fabric. It is in reflecting this 21st century world back to audiences, both within China and in the West, that artists ‘serve the people’ today. If you want to read on, click on this link: http://theartlife.com.au/2013/serve-the-people/

4. Shoufay Derz, Owen Leong and Cyrus Tang, Phantom Limb, UTS Gallery, September 2013

|

| Shoufay Derz, On the other hand (detail), concept image for sculpture, 2013. Natural Indigo, blown borosilicate glass fountain pens, gold plated nibs, sandblasted black granite, black Chinese ink. Image source http://www.cofa.unsw.edu.au/events/archive/935 |

| Three really interesting artists in an exhibition which explored "disembodiment and the attempt to bridge a physical or metaphysical divide." |

In the interests of what politicians like to call 'full disclosure' I have to declare that Shoufay Derz is a friend and colleague, however that does not alter the fact that I consider her unequivocally one of the most interesting artists working in Sydney right now. Her commitment to a deeply philosophical practice based on her research and investigation of religion, philosophy, art and cultural history and the embodiment of materiality is impressive. She followed this exhibition with a show at Artereal Gallery (link here: http://arterealgalleryblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/luise-guest-on-shoufay-derz.html) and is currently completing a residency in Taipei. I look forward to seeing what she will do next.

|

Shoufay Derz, I Am Death, Destroyer of Worlds, image courtesy the artist

|

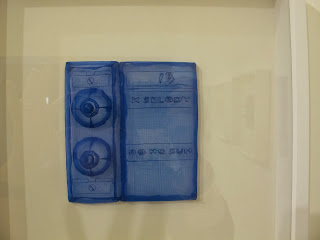

5. Yin Xiuzhen, 'Nowhere to Land' at Pace Beijing, October 2013

|

| Song Dong and Yin Xiuzhen at their Beijing studio, November 2013, photograph Luise Guest |

.jpg) |

| Yin Xiuzhen, Portable Cities, Biennale of Sydney 2003, image courtesy the artist |

I have loved her work since I saw the whimsical 'suitcase cities' at the Biennale of Sydney many years ago (seen again this year at the Moscow Biennale.) This exhibition was a revelation - her use of old discarded clothing is powerfully evocative and I particularly loved the moody, atmospheric paintings of Beijing streetscenes on cement road barriers. She combines whimsy and wit with a passionate and intelligent focus on issues and ideas. After I saw the exhibition, on my first visit to 798, I was determined to find a way to meet the artist. It took until the end of my residency, in the very last week, before we managed to arrange a time, and it was a highlight of my time in China. I just hope to have the opportunity at some point to see the wonderfully witty 'Collective Subconscious', shown at MOMA in 2010.

|

Installation view: Yin Xiuzhen. Collective

Subconscious. 2007. Minibus, stainless steel, used clothes, stools, music.

Collection of the artist. © 2009 Yin Xiuzhen. Photo: Jason Mandella.

|

When I met Yin, with her husband Song Dong, at their studio out near the Great Wall, she told me that her intention with these painted works was to reflect on China's appalling and worsening air pollution. She fears for her daughter, and sometimes feels hopeless and despairing. She said, "They (these paintings) may look beautiful and misty, but in fact they are poisonous." The visit was not without drama. Mr Zhang, my driver, nearly had a heart attack when he saw the complicated directions in their text message, which took up 3 or 4 screens and went along the lines of: "After you leave the expressway, drive past a group of dead trees, then when you see a factory with a red gate, take the next road on the left over a small bridge. Drive for a while. You will see a blue sign on a fence. Turn right at the next village....etc." We got lost many times, asking directions from farmers, factory workers, and women riding bicycles along the dusty road. The drive from central Beijing took nearly two hours and the drive back, in traffic that caused the usually placid and unflappable Mr Zhang to swear continuously and viciously, took three. As we left,and Song Dong and Yin Xiuzhen were waving us goodbye from their gate, he asked dubiously, "Tamen youming ma?" (Are they famous?) I said, "Dui ah, tamen shi zhende hen, hen, feichang youming yishujia!" Which is bad grammar but gets the emphatic point across.

|

| Yin Xiuzhen, Traffic Barrier, Chang'An, from solo show 'Nowhere to Land' at Pace Beijing, image source: ocula.com |

6. Qiu Zhijie 'Satire' at Galleria Continua, 798, Beijing, November 2013

Weird and slightly incomprehensible, but oddly fascinating as this artist always is. When I went to his talk at the MCA last year and he presented his concepts for the Shanghai Biennale, I left the lecture theatre thinking that either I am very, very stupid ( always a possibility) or else that Qiu Zhijie is a very charming but alien being from a far far galaxy. His exhibition confirmed for me that while he may not actually be an extraterrestrial, he certainly doesn't think like other people.

|

| Qiu Zhijie, 'Satire' at Galleria Continua, Beijing, installation views, photographs Luise Guest |

7. Yinka Shonibare at Pearl Lam Hong Kong in December 2013

To tell the truth, the major Yinka Shonibare show at the MCA in Sydney some years ago left me a little cold - I thought the messages about postcolonialism were obvious and a bit trite. The new show at Pearl Lam was different - multiple meanings and some witty and satirical views about Hong Kong's obsession with wealth and status as well as the fabulous characteristic use of textile patterns.

8.

Do Ho Suh at Lehmann Maupin Hong Kong, December 2013

What can I say? His work is profound, beautiful and spellbinding, even in the context of this extremely swanky gallery where I had trouble attracting attention to ask for a catalogue because they were very busy doing a high pressure sales pitch to a glamorous, designer-clad, Chinese buyer.

9.

No Country: Contemporary Art for South and South East Asia, Asia Society Hong Kong, December 2013

This was unexpectedly fantastic. One of the best curated exhibitions I saw in 2013, in fact. Curated by June Yap under the auspices of

the Guggenheim UBS MAP Global Art Initiative , the exhibition included some artists whose work I know (

Shilpa Gupta) and others who were new to me. My favourite was Bangladeshi

Tayeba Begum's 'Love Bed' - a little bit Mona Hatoum, a little bit Lin Tianmiao, a little bit Ed Kienholz but without being merely derivative. And absolutely chilling.

|

| Love Bed, 2012. Stainless steel, 31 1/4 × 72 3/4 × 87 inches (79.4 × 184.8 × 221 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Guggenheim UBS MAP Purchase Fund, 2012, 2012.153. © Tayeba Begum Lipi. Installation view: No Country: Contemporary Art for South and Southeast Asia, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 22–May 22, 2013. Photo: Kristopher McKay |

The catalogue provided insight without empty 'artspeak'.

"For the artist, the nation’s political state forms the backdrop to another critical political concern: the gendered violence that was rife during both partitions. Her works reflect on both the double bind of the personal and the political, expressing and accentuating a sense of unease through a public form of gendered expression that also speaks to challenges faced by the artist and her contemporaries. In Bizarre and Beautiful (2011), exhibited at the inaugural Bangladesh Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale, she transformed mock stainless-steel razor blades into the fabric of a feminine undergarment. Attractive yet threatening, the article is converted into a hard, gritty form, possessing the qualities of armor or a shield.

Razor blades return in Love Bed (2012), in which the shared space of domesticity, affection, and bliss glints with both threat and invitation. The blade here represents not merely the violence implied by its sharp edge, but also the object’s function as a basic tool to aid in childbirth in the absence of other medical support, a circumstance that the artist recalls from childhood. Printed on the blades is the Bengali name Balaka, a well-known Bangladeshi brand. Coming from a large family, the artist associates the strength of steel with the tenacity of the women who surrounded her as she grew up, individuals who defied the odds to keep their families and communities together. Yet these works resist interpretation according to simple binary opposition along historical, religious, social, or gendered lines. As much as the skeins of razors draped across the bed frame warn against our approach, they also, paradoxically, join together into a productive space for connection and dialogue."

|

| Zhou Hongbin, image courtesy the artist and China Art Projects |

10. Two exhibitions at the CAP Project Space in Sheung Wan, Hong Kong which neatly bookended my 3 months in China - the first, 'Aquarium' by Chinese photomedia artist Zhou Hongbin (definitely someone to watch) and the second, a show of new artists from Sri Lanka, 'Serendipity Revealed'. This last contained the extraordinary images of Anoli Perera.

|

| Anoli Perera, 'Protest', black and white photograph |

I also enjoyed

'I Am Your Agency',

Jing Yuan Huang's November solo show at Force Gallery in 798, and

'I Love Shanghai', a group show at Art Labor Gallery which included works by

Lu Xinjian, the ubiquitous Island6 (Liu Dao) collective - are they actually literally

everywhere? - Emma Fordham (she's an art teacher - yay!) and a stunning photograph of the transformation and loss of old Shanghai, by

Greg Girard.

I also loved the concept behind Redgate Gallery's November show, which paired printmakers with significant Chinese poets. 'River on Paper' included some of the printmakers that I had met earlier in the month at the Xi'an Academy of Fine Arts, and it was a delight to discover some of the poems as well.

|

River on Paper - Dialogue between Poetry and Prints

Lies, Poet: Zhai Yongming, Artist: Kou Jianghui, 2013, Lithograph, 56 x 38 cm, part of the River on PaperPortfolio, 2013, Boxed, 61 x 42 cm, image Redgate Gallery http://www.redgategallery.com/Exhibitions%201991%20-%202013/River_on_Paper/index.html

|

Earlier in the year I really loved

Tianli Zu's work at 4A Centre for Contemporary Art in the group show

'In Possible Worlds'. And who could forget John Kaldor's '

13 Rooms' - not all fabulous but the re-creation of the Marina Abramovic piece was extraordinary as was Xu Zhen's 'Blink of an Eye'.

|

| Xu Zhen, 'In the Blink of an Eye', image source: www.smh.com |

I won't be negative and focus on the disappointments. But they included, most especially, the

Hugo Boss Asian Art Awards at the Rockbund Museum Shanghai - this left me completely cold and utterly disengaged. So disappointing, as the show there last December which included Huang Yong Ping was one of my 2012 highlights. I was left unexcited by much of the

Asia Pacific Triennial early in the year as well - unexpected as every previous show has been fantastic. I suspect that sourcing so many artists from Micronesia and Central Asia and pretty much ignoring China may have been one of the factors that left me less than impressed there. Not that I am biased or anything. And to even the balance, the new

Fang Lijun show in 798 was very, very dull. I don't think he should bother returning to Jingdezhen to do any more slumped, fallen, collapsed ceramic pieces, frankly.

What am I looking forward to? Cai Guo-qiang at the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art next week - watch this space! Christian Boltanski at Carriageworks in January. And Beijing Silvermine at 4A Centre for Contemporary Art - intriguing!

What were your highlight exhibitions this year?

Happy New Year! 新年快乐!Xinnian Kuai Le!

May 2014 (the year of the horse) be filled with interesting art, and fascinating conversation.

,+2013,+oil+on+canvas,+121+x+160.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)