Cruising lazily out of the choppy seas of 2015 and into the uncharted waters of 2016 I have been reviewing experiences of Chinese art, and China, and doing that very cliched thing: making a list. I've read so many of these in the last few days. Lists of the best and worst of the year are metastastizing everywhere, from movies and music to food fads (kale is gone, you'll be glad to know) to the most over-used words of 2015 (''bae'', apparently, and I am sadly so out of touch with popular culture that I could not tell you what it even means) The list mania appears to be contagious. I decided to launch into my own "best of" compilation of art highlights - and a few lowlights. It's entirely personal; my retrospective musings over a year filled with art, mostly Chinese.

1 January saw Sydney audiences enthralled by the ever-so-slowly crumbling face of a giant Buddha made of ash from the burned prayers of temple worshippers in China and Taiwan. Zhang Huan, having reinvented himself entirely from his earlier persona as the bad boy of '90s violently masochistic performance art, presented this latest iteration at Carriageworks. And it was rather wonderful. I wrote about meeting the artist and encountering the silent presence of 'Sydney Buddha' for The Art Life. Click HERE for the story.

|

| Zhang Huan, 'Sydney Buddha'' installed at Carriageworks, image courtesy the artist and Carriageworks

2 January also saw some younger Chinese bad boys hit town - the Yangjiang Group arrived with their unique brand of artistic anarchy for a crowd-funded project, 'Áctions for Tomorrow', at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. Along with a bunch of other bemused scribes I had tea with the artists. So. Much. Tea. It was an artwork, and we were part of the art. Previously their performances of 'Fan Hou Shu Fa' (After Dinner Calligraphy) had involved prodigious feats of alcohol consumption, but they now stick mainly to tea, which they had brought with them from their home in Guangdong Province. What did we see in the gallery? Wax dripped over a shop full of mass produced clothing to create a frozen monument to retail therapy? Check. An installation of the remains of 7,000 sheets of paper covered with text from Marx’s Das Kapital in Chinese calligraphy, over which simultaneous games of soccer had been played? Check. A 24-metre mural juxtaposing expressive Chinese characters with scrawled English text reading “God is Dead! Long Live the RMB!”? Check. When I presumptuously asked if this last had a connection with their views about a materialistic new China, Zheng Guogu shook his head sadly at my outdated desire to find meaning. That's entirely beside the point, he said. Anti-art? To misquote the Chinese Communist Party’s description of socialism in the global marketplace, perhaps this was “dada with Chinese characteristics.” I wrote about my interview in Daily Serving. Click HERE for the story.

|

|

| The Yangjiang Group at 4 A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art (Zheng Guogu in centre) photo: Luise Guest |

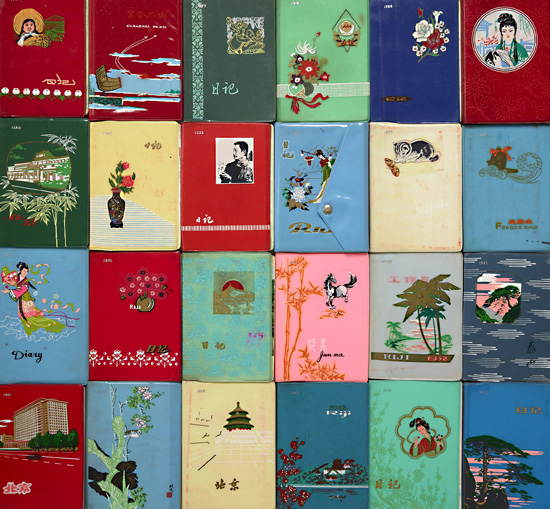

3 In February I was a little bit preoccupied with arranging a wedding, and I have zero recollection of March to April. May brought the Sherman Foundation exhibition of Yang Zhichao's 'Chinese Bible'. Yang is another Chinese performance artist becoming a little less inclined in middle age to punish his own body with the surgical insertion of various objects - reputedly at the insistence of his daughter. Chinese Bible is a beautiful and important installation - part art, part anthropology, part social action. Not unlike his good friend Ai Weiwei, Yang Zhichao made a formalist, minimalist arrangement of found objects, some dating from the Cultural Revolution.

“Historical experience is written in iron and blood,” said Mao Zedong. In Chinese Bible, historical experience is written in thousands of humble, mass-produced notebooks once owned by ordinary Chinese people, their worn covers testament to the weathering of time and the vicissitudes of social change. Ai Weiwei says, “Everything is art. Everything is politics,” and Chinese Bible reveals a similar approach to art as a form of social engagement. I interviewed Yang Zhichao at SCAF with the translation assistance of Claire Roberts, who curated the show and had written a most wonderful catalogue essay. They told me that after the installation, on their way to a celebratory lunch in Chinatown, they asked their Chinese taxi driver if he would like to see the exhibition. He said he could not possibly, his memories are so painful it would make him weep. Later, in October, I met sculptor Shi Jindian at his home and studio in the mountains outside Chengdu. Disarmingly humble, polite and hospitable, as the day wore on he was becoming monosyllabic and I was worrying about why my interview with this artist was proving to be such hard going. He suddenly said, "I have lived through every period of recent Chinese history, and it was all terrible. I don't want to talk about the past." Like the Sydney taxi driver, and for so many others of his generation, there are just too many bitter memories. You can read the article and my interview with Yang Zhichao HERE.

|

| Yang Zhichao, Chinese Bible, 2009 (detail, 3,000 found books, Dimensions variable Image courtesy: the Gene and Brian Sherman Collection, and Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation, Sydney Photo: Jenni Carter AGNSW |

|

| Lin Tianmiao, Badges 2009 White silk satin, coloured silk threads, gold embroidery frames made of stainless steel; sound component: 4 speakers with amplifier. Dimensions variable, diameters range from 25 cm - 120 cm, 266 badges total. Image courtesy: The Gene & Brian Sherman Collection, and Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation, Photo: Jenny Carter |

4 In the second part of this exhibition, 'Go East' at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, curated from the Sherman collection by Suhanya Raffel, it was wonderful to finally see Lin Tianmiao's 'Badges' hanging in the imposing domed vestibule. Visiting her studio in 2013, I had watched her assistants stitching the texts, words describing women in Chinese and English, onto embroidery hoops. I had wondered what they were thinking as their nimble fingers stitched words like "Slut", "Whore" and "Fox Spirit" (a terrible name for a woman in Chinese.) I was amused in Sydney, where all the badges were Chinese, to encounter shocked groups of Mandarin speaking tourists making their children look the other way. In this show, in addition to works by Zhang Huan and Song Dong, Yin Xiuzhen's 'Suitcase Cities' were a highlight. A newly commissioned work by Ai Weiwei intrigued my students. ‘An Archive’ is a collection of the artist’s blog posts, banned since his efforts to name the children killed in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake attracted the attention of the authorities, presented in the form of traditional Chinese books in a beautiful timber box. A clever and more than usually subtle representation of Ai's resistance to the censorship and constraint that saw him confined to Beijing without possession of his passport, constantly under surveillance, until 22 July this year.

|

| Kawayan De Guia. Bomba, 2011; installation comprising 18 mirror bombs, sputnik sound sculpture; dimensions variable. Collection of Singapore Art Museum. Courtesy of Singapore Art Museum |

|

| Shen Shaomin. Summit (detail – Ho Chi Minh), 2009; silica gel simulation, acrylic, and fabric; dimensions variable. Singapore Art Museum collection. Courtesy of Singapore Art Museum.

6 August was about planning and organising my own reinvention, from one kind of life to another, and in September I went to China for 5 weeks, to interview artists for a new project, which (of course) provided more highlights. Of these, perhaps the most remarkable was my visit to the studio/manufacturing hub of Xu Zhen and the MadeIn Company, in Shanghai. You would have to have been wearing a blindfold or lived in a cave to remain unaware of Xu Zhen, who appears to have taken on the mantle of Andy Warhol (although he told me that his favourite artists are Jeff Koons and Matthew Barney.) His enormous installations merge art and commerce, art and design, east and west, past and present, and any other form of post-internet hybridity you care to mention. He will feature in the 2016 Biennale of Sydney, and the work of the artist and his company of assistants and employees has been seen simultaneously in almost as many locations as the ubiquitous Ai Weiwei. (Although Xu Zhen himself does not fly, so everything is arranged and organised, and all research outside of China completed, by teams of MadeIn employees.) A focus artist at the 2014 New York Armory Show, and one of my top picks of last year for the spectacle of his retrospective exhibition at Beijing's Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Xu Zhen is given to gnomic Warhol-like utterances. "Chinese contemporary art nowadays is a farce filled with surprises," he told Ocula. 'Eternity' has been wowing audiences at the White Rabbit Gallery since early September. And watch out Sydney, there is a promise of more to come!

|

|

| Xu Zhen by MadeIn Company, Eternity, 2013-2014, glass-fibre-reinforced concrete, artificial stone, steel, mineral pigments, 15 m x 1 m x 3.4 m image courtesy White Rabbit Collection |

7 And so to Shanghai in late September, and a major highlight of my year: the exhibition of an artist who should be a household name. Chen Zhen died (much too young) in Paris in 2000. Although after 1986 he essentially lived and worked in Paris, his personal history and deep cultural roots lay in China, and specifically in Shanghai. From the mid-1990s he returned over and over to a city on fast-forward. Shanghai was undergoing a massive, controversial transformation, in the process of becoming the global megalopolis it is today. The exhibition at Shanghai’s Rockbund Art Museum presented works from this period. Sometimes witty, sometimes profoundly beautiful and melancholy, Chen Zhen’s works are steeped in his identity as a Chinese artist at a historical “tipping point.” As the artist said in his online project Shanghai Investigations, “without going to New York and Paris, life could be internationalized.” To finally see 'Crystal Landscape of the Inner Body' was a revelation - both sad and beautiful. HERE is the whole story.

|

| Chen Zhen. Crystal Landscape of Inner Body, 2000; crystal, iron, glass; 95 x 70 x 190 cm. Courtesy of Rockbund Art Museum and Galleria Continua San Gimignano/Beijing/Les Moulins. |

|

| With Wang Qingsong in his Studio, October 2015, Caochangdi, Beijing |

8 is for Beijing, in October, and meetings over three action-packed weeks with a ridiculous number of interesting artists, all represented in the White Rabbit Collection. Old friends and new faces: Bu Hua, Bingyi, Li Hongbo, Zhu Jia, Wang Qingsong, Wang Guofeng, Liu Zhuoquan, Qiu Xiaofei, Lin Zhi, Huang Jingyuan, and Zhou Jinhua. Dinners with friends, long walks through the hutongs and the never-ending struggles of language learning. I journeyed through the smog to studios on Beijing's far outskirts, collecting stories and looking at extraordinary work, as I had done the previous week in Shanghai and Hangzhou. I left China with a kaleidoscope of impressions that are just starting to crystallise into the possibility of words. I saw Liu Xiaodong at the Faurschou Foundation and Ai Weiwei at Continua, but disappointingly missed Liu Shiyuan in Shanghai at the Yuz Museum. One of the youngest artists I interviewed in 2013 and 2014, her work will next show at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, in an exhibition curated by Philip Tinari, among others, called 'Bentu: Chinese Artists in a Time of Turbulence and Transformation.'

9 is another repeat of one of my 2014 picks. The rather bizarre Red Brick Museum (practically empty on each occasion I have visited) on Beijing's northern outskirts was showing work by the artist who first inspired me to make Chinese art my focus of research, teaching and writing. Huang Yong Ping's fabulous thousand armed goddess of mercy was an unexpected delight when I visited in December of 2014. Again, in 2015, a new exhibition, curated by Hou Hanru (also the curator of the Chen Zhen show in Shanghai) presented a version of Baton - Serpent, seen in a previous Asia Pacific Triennial in Brisbane. Not quite the 'words fail me' experience of seeing Leviathanation at Tang Gallery in 2011, or the 'Thousand Armed Guanyin' at the Shanghai Biennale in 2012, but nonetheless extraordinary. And all the more wonderful for being encountered in the deserted echoing spaces of one of China's newest museums.

10 And here we are, washed up on shore, arrived at the final, dog days of 2015.

November to December, hmmm. What to pick? NOT 'Ai Weiwei and Andy Warhol' at the NGV. If you have read my review (Click HERE if you want to) you know I had some issues with that exhibition - although I wish I had seen the London show at the Royal Academy. I admire Ai enormously for his genuine commitment - particularly his establishment of a studio on Lesbos to make art relating to the current refugee crisis. But boy oh boy did I hate those Lego portraits. And absolutely NOT the 'Rain Room' at the Yuz Museum in Shanghai - an empty spectacle. Nor anything at the major Sydney galleries - I cannot get excited about a few Renaissance works from Scotland, and Grayson Perry, whilst interesting, does not float my boat. ![Image 1 [Digital Photography_Colour Photograph] Dwelling - Moment III small file](http://theartlife.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Image-1-Digital-Photography_Colour-Photograph-Dwelling-Moment-III-small-file.jpg)

YUAN GOANG-MING Dwelling - Moment III 2014. Digital Photography / Colour Photograph.

120 x 180 cm Edition of 8. Image Courtesy of the Artist and Hanart TZ Gallery.

I'm giving my Number 10 highlight spot to Yuan Goang-ming at Hanart TZ in Hong Kong. In this show, entitled Dwelling, we were presented with the uncomfortable intersection of the real and the apparently impossible. In the gallery space, an elegant table was laid as if for a dinner party, with crystal glasses and an ornate dinner service. Every now and then a loud clanking noise disrupted the silence, and the table shook as if the building had been hit by an earthquake. In the title work, Dwelling, (2014) the focus is a blandly modern living room, the only oddity the rather slow riffling pages of a magazine on the chair, a book on the coffee table. A breeze wafts the curtains. Suddenly, and without warning, the entire room explodes. Slowly, languidly, the wreckage of the room drifts back until the room once again regains its ordinary appearance. Filmed

underwater, although it takes a while to realise this, the movement of every object seems dreamlike. Yuan suggests that what we accept as stable and fixed is in fact entirely unpredictable. In a split second, the apparently impossible can disrupt everything we take for granted.

In my own 2015 version of the impossible becoming possible, I have changed careers, started new research and writing projects, and - in a total triumph of optimism over bitter experience, I enrolled in a new term of Chinese language classes.

Oh. And I have written a book. Out in February.

|