|

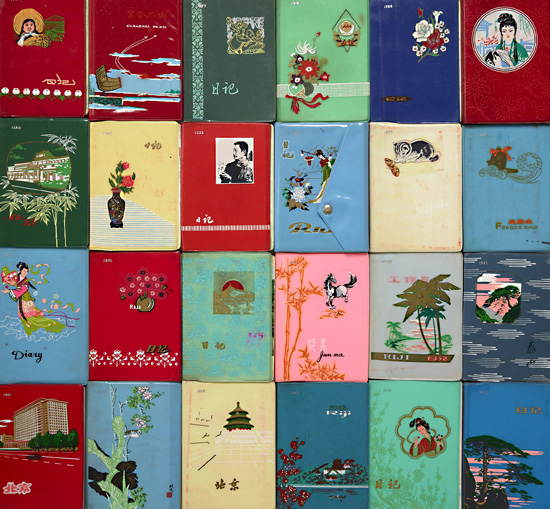

| Pixy Liao, 'Things We Talk About', 2013, image courtesy the artist |

In normal times at this tail end of the year I would write a kind of 'best of'' list of the art, the exhibitions and the most memorable artworld moments of 2020. I know, I know, it's kind of lame and a cliched media trope, but I have always enjoyed looking back over my calendar and sorting through all the many and varied experiences. Well, as we all know, these are not normal times, and this year there are vanishingly few things to talk about. The lasting experience of 2020 is of solitude mixed with uncertainty, boredom, and occasional lapses into existential despair. Life became very small as I encountered my students and colleagues mostly on Zoom, and seized precious socially distanced opportunities to see family and friends. I have tried to be more aware of the natural world, the turning of the leaves, the singing of birds in the garden, the sunsets and the moon - but frankly I'm often reading or watching Netflix and shamefully I see the moon and the sunsets in other people's Instagram photos more often than in reality. And as for art.....

The final exhibition I saw before the onset of Sydney's lockdown in March, somewhat nervously due to the increasingly serious pandemic, was 'Xu Zhen: Eternity Vs. Evolution' at the National Gallery. I felt that the visceral spectacle of the works, which had been so evident in the major survey exhibition at Beijing's UCCA and in various shows at White Rabbit Gallery, was somehow diminished inside the rather dark concrete spaces of that Brutalist Canberra building.

|

| XU ZHEN® "Hello", installation view, Photograph: Luise Guest |

The best critical account of that exhibition is by Alex Burchmore, in Randian. Of the snake-like, moving Corinthian column activated by visitor movement he writes: ''the voluptuous coils of ‘“Hello”’ (2019) take pride of place in ‘Eternity Vs Evolution’, towering over the viewer and following their every move with a baleful gaze that threatens consumption by the emptiness of the void (and note the inclusion of quotation marks in the title). The caption for this work draws attention to the historic prestige of the Corinthian column that Xu has chosen for the body of his serpent, ‘first created in ancient Greece [as] a symbol of power, prestige and western civilization.’ Yet the flaccid immobility of this automated guardian, save for the hesitant and creaking sway of its pediment-head when activated by the approach of the viewer, inspires more pity than dread. Carved in soft and yielding Styrofoam, this is a column devoid of all function, a structural support incapable of supporting its own weight, spectacular in scale but hollow within. As such, ‘“Hello”’ offers a clue to the underlying message of the exhibition: that which seems invulnerable and eternal is often little more than an artfully contrived illusion, while the evidence of our own eyes is rarely as straightforward as it seems and inevitably colored by the assumptions that structure our view of the world.'' Read the full article here.

Vermilion Art, 'To Live [It Up]', was also interesting, providing a different view of the artist's work than the big survey show of his career that I had seen at Ink Studio in Beijing in 2019. It's great to know that a number of works were acquired from this exhibition for the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

|

| Works by Li Jin shown at Vermilion Art in November |

So, in this globally calamitous and personally very challenging year, how to make some sense out of the chaos and confusion? Is it even possible in this year when the president of the United States is advocating a literal military coup to contest an election he lost, and when so many of us have lost faith in our governments' responses to the pandemic that has devastated the globe. We are increasingly divided, angry, sad and cynical.

Among the many losses of the year, a bright spot for me was the realisation that it was still possible to continue my conversations with Chinese artists, albeit (sadly, and who knows for how long) not face to face in their studios. I've spoken with Pixy Liao, Cao Yu, Liu Xi and Shoufay Derz via email, Facebook and Wechat and have had articles published in a range of print and online journals that I've referenced in previous blog posts, including most recently an article in Art Monthly Australasia.

|

| Pixy Liao, 'Ít's Never Been Easy to Carry You', 2013, image courtesy the artist |

These conversations were interesting and thought-provoking, challenging some of my assumptions about art, feminism and China, which is always a good thing. I take these ideas now into the chapter for a book that I am working on, so watch this space! Here is the opening section of the Art Monthly piece. In the extract below I've left out the footnotes and references, just to make it more readable in this blog format:

'Public Bodies, Private Lives: the work of Cao Yu and Pixy Liao'

In the cold Beijing winter of 2012, I interviewed

Lin Tianmiao – often described as one of very few feminist artists in China. She

told me bluntly, ‘There is no feminism in China. It’s a Western thing.’She meant, I think, that Euro-American feminism/s were not especially relevant

to the experiences of Chinese women – and also that she resisted being silo-ed in

a still-patriarchal Chinese artworld as a ‘woman artist’. It is generally acknowledged, as Shuqin Cui recently argued, that

‘few Chinese women artists would welcome the label of feminist art or

categorize their work as feminist art even if the feminist dimensions of their

work were clearly evident.’ Nonetheless, many

artists grapple with issues of gender and challenge heteronormative stereotypes. A feminist self-identification is not especially significant, as art historian

Joan Kee noted: ‘The question

is not whether women artists from Asian countries identify themselves as

feminists, or whether their work imparts feminist messages. Instead, the issue

concerns the logic of interpretation’. Feminism is embodied in nuanced and culturally specific

ways in the practice of many contemporary Chinese artists – even if they disavow

the label. When

I spoke with multi-disciplinary artists Cao Yu and Pixy Liao, they expressed

reservations about being pigeonholed, yet their work powerfully challenges essentialist

notions of the ‘feminine’.

|

| Cao Yu, 'Mother' series, installation view, image courtesy Cao Yu and Urs Meile Beijing/Lucerne |

|

| Cao Yu, 'Everything Will Be Left Behind', installation view (above) and detail (below), image courtesy the artist and Urs Meile Beijing/Lucerne |

Perhaps, at the end of a year that has been so terrible for so many across the globe, at the mercy of a virus (and I don't mean the one in the White House) we come back to the knowledge of our tiny insignificance in the vastness of the universe. Lately I am finding that comforting rather than frightening. The title of Lindy Lee's exhibition 'Moon in a Dewdrop' is a reference to the writings of Dōgen, the 13th century Zen monk who brought Buddhism from China to Japan. Lee is a practising Buddhist and the philosophy informs her life and art. I think of the artists I know in China whose study of Daoism similarly inflects their work, and their reactions to the world and its suffering. We too are the 'ten thousand things' - everything under heaven - in a constantly fluxing relationship with the world and everything in it - light and dark, health and illness, solitude and companionship. Well, I'm working on that level of acceptance. Mostly failing. It's a process.

Lindy Lee, Buddhas and Matriarchs, 2020,

installation

view, Lindy Lee: Moon in a Dew Drop, Museum of Contemporary Art

Australia, Sydney, 2020, flung bronze, image courtesy the artist,

Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney and Singapore and the Museum of Contemporary Art

Australia, Sydney with the assistance of UAP and © the artist,

photograph: Anna Kucera

As Dōgen said of himself watching the moon:

‘Sky above, sky beneath, cloud self, water origin’

![Image 1 [Digital Photography_Colour Photograph] Dwelling - Moment III small file](http://theartlife.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Image-1-Digital-Photography_Colour-Photograph-Dwelling-Moment-III-small-file.jpg)