|

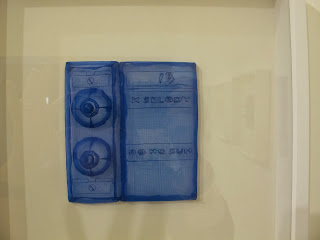

| Song Dong, Wisdom of the Poor: Song Dong’s Para-Pavilion, Old house, old furniture, steel, Dimensions variable. 2011. Image courtesy Rockbund Art Museum |

In Shanghai at the end of April I was lucky -- so lucky -- to catch the last weeks of this show, a survey of 30 years of Song Dong's work. From his earliest performance works, lying flat on the frozen ground in Tiananmen Square and breathing, or stamping the surface of the Lhasa River in Tibet with a seal carved with the character for 'water', to works based on his extended series of 'para-pavilions', architectural structures made from re-purposed furniture and building remnants, the show was a marvel across the six levels of the museum. For a review published in 'The Art Life', I described it like this:

I Don’t Know the Mandate of Heaven’ is a mature artist’s reflection on life’s joys, dreams, fears and disappointments. Beijing-based conceptual artist, Song Dong, responds to one of the Analects of Confucius, in which the sage suggests that by the age of 50, one ought to be sure of one’s place in the universe, should know ‘the mandate of heaven’. The getting of wisdom, if you like, should be done and dusted. Across six floors of Shanghai’s Rockbund Museum, and across its façade, rooftop balcony, stairwells and elevators, Song Dong responds to Confucius with all the uncertainty and anxiety of a more complicated age: ‘At 10, I was not worried. At 20, I was not restrained. At 30, I wasn’t established. At 40, I was perplexed and at 50, I don’t know the mandate of heaven.’

The exhibition is divided into seven ‘chapters’, one for each floor of the museum and the seventh for the exterior. Each chapter is represented by a Chinese character; together they form a line of a verse:

Jing (mirror), Ying (shadow), Yan (word), Jue (revelation),

Li (experience), Wo (self), and Ming (illumination).

Entering, you are immersed in a structure of re-purposed window frames and mirrors, a (literal) Daoist reflection on the fleeting nature of the physical world, beautiful and unsettling. Within the structure you find Song’s homage to Duchamp’s first readymade. The Use of Uselessness: Bottle Rack Big Brother (2016) is an enlarged version of Duchamp’s inverted bottle rack; on its prongs are discarded bottles that once held whiskey or powerful Chinese baijiu. Lit to resemble a fallen chandelier, they have been cleverly arranged to look a lot like the ubiquitous surveillance cameras that watch our every waking moment. This modern day panopticon has particularly chilling connotations in China, and the work reminds us that surveillance has been a recurring theme in Song’s work. To read more, click HERE

2. "Jasper Johns, Something Resembling Truth", Royal Academy, London, October

While I loved visiting old favourites on my blink-and-you'll-miss-it work trip to the UK in October (obligatory visit to Holbein's Ambassadors, the odd Titian and Raphael, and my favourite bizarre Annunciation by Carlo Crivelli) only one London exhibition really excited me, another survey. An artist of almost Chinese longevity, Jasper Johns has produced consistently interesting work since the late 1950s and this exhibition, the first comprehensive survey to be shown in the UK in 40 years, revealed the shifts and developments in his six decades of practice. Many works I had only seen before in reproduction, such as the Four Seasons paintings; other, more recent, work was completely new to me. Johns continues to experiment with form and content, defying stereotypes of the aging artist repeating the tropes of their youth. In the grand, hushed surrounds of the Royal Academy, visitors murmured discreetly, a very different experience from being amongst the young Chinese audience at Song Dong, taking selfies and giggling.3. Qiu Anxiong, "New Book of Mountains and Seas Part III" at Boers-Li Gallery, Beijing, April

Immersive and extraordinary, Qiu Anxiong's final work in this trilogy is a frighteningly dystopic twist on the present day. Adding a newly high-tech gloss to Qiu's technique of animating his ink drawings, the work conveys themes of twenty-first century anxiety and alienation expressed through the metaphor of the metropolis. It's probably no wonder that speculative fiction is big in China, although I often feel that nothing could be stranger than reality.

4. Zhou Li, Yuz Museum, Shanghai, April

In her first solo exhibition for many years, Zhou Li's works completely seduced me. In a darkened space on the upper level of the huge Yuz Museum on the West Bund, her abstract canvases glowed. Floating shapes hover on soft grounds of grey, or occasionally, of vivid red or pink. Linear forms overlap, abut and coalesce, suggesting the constant rhythms of the universe. Zhou, like many contemporary Chinese artists, is interested in Daoist philosophy: the push and pull of yin and yang are discernible in her juxtapositions of line, colour and form.

Here's a description of the show from ARTFORUM

In 2017 I have been fortunate to have conversations with many artists, both in Sydney and in China. As part of an archive project for the White Rabbit Collection, I have recorded interviews with Guo Jian, Song Yongping, Lu Xinjian, Xiao Lu, Lin Yan, Song Jianshu, Xia Hang, Cang Xin, Wang Zhiyuan, Huang Hua-Chen and Shen Jiawei. You can find these videos HERE. For my own ongoing research project I have re-interviewed Xiao Lu, Ma Yanling and Tao Aimin in Beijing, and for yet another project I've met with Shi Yong in Shanghai. Courtesy of the Vermilion Art stand at Sydney Contemporary, I engaged Cang Xin in conversation about his life and work as a post-89 conceptual artist. All of these conversations have been fascinating, but two that have been especially memorable were my second visit to the studios shared by Yu Hong and Liu Xiaodong, in Beijing, and a long conversation over cups of coffee in the British Library Cafe with performance artist Echo Morgan (aka Xie Rong).

|

| Yu Hong, One Hundred Years of Repose, 2011, Acrylic and gold leaf on canvas, Image courtesy the artist |

|

| Yu Hong in her Beijing studio in 2014, Photo: Luise Guest |

|

| Echo Morgan, Be the Inside of the Vase, 2012, Performance Still, image courtesy the artist |

And the 'Half a Dozen of the Other'?

Best not to dwell. Disappointments in 2017, apart from the sense of impending doom shared by all sentient beings in a time of Trump, included the David Hockney exhibition at the NGV, some lacklustre shows at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and a truly awful exhibition by ''KAWS" at the Yuz Museum in Shanghai, to which the only possible response was "WTF". I'm sad not to have been able to see THAT Chinese show at the Guggenheim, nor the earlier "Tales of Our Time", but, hey, you can't see everything. Onward to 2018, to a new Biennale of Sydney, curated by Mami Kataoka, to a visit to Melbourne to the first NGV Triennial, the 9th Asia Pacific Triennial in November, some exciting shows coming up at White Rabbit Gallery, building on the beautifully curated 'The Dark Matters' and 'Ritual Spirit', and to further adventures in China and elsewhere. And a heartfelt New Year's resolution to work harder on my Chinese. We'll see. Meanwhile, a happy and prosperous 2018 to all readers of this blog!

|

| With Cang Xin, courtesy of Vermilion Art, at Sydney Contemporary (we did not exchange clothing!) |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)