Thus it was that on a cold, windy day recently I found myself waiting for Guan Wei in the surreal environment of the big outlet malls on Beijing's outskirts, which look more Rodeo Drive than Chang'An Avenue. When he pulled up beside me he assured me he has never been inside them - and the idea of him shopping among the fake designer brands and factory seconds of Burberry and Louis Vuitton (or perhaps Burberrk - yes I have really seen this one - or Louis Vuillon) is a little hard to imagine. He is a larger than life figure with an infectious laugh and an engaging turn of phrase. I was intrigued to find out more about his life now, as he moves between his Sydney and Beijing studios. He told me he prefers Beijing in the winter as Sydney summer heat is too much for him.

|

| With Guan Wei in his Beijing studio, November 2013 |

What follows is an account of my interview with him, published in 'The Art Life' today.

Guan Wei is a story-teller, a myth-maker and a social commentator. He is also a fabulist who blends real and imaginary histories, both Chinese and Western, in order to create a parallel universe, a floating world which invites us to question our cultural certainties. He has said that he likes to work in the space between imagination and reality, and his work is deeply personal, reflecting his unique experience of the world, and of a hybrid identity, moving between cultures. He is perhaps the most significant artist currently working between Australia and China, showing regularly in Sydney, Melbourne, and Adelaide as well as Beijing, Suzhou and Shenzhen. His characteristic imagery of pink fleshy faceless people, Chinese clouds and swirling seas, mythological beasts and disembodied Buddha hands is well known and distinctive. However, he is not an artist who stands still, nor is he content to merely repeat what has brought him success, as I found when I visited him this month in his Beijing studio.

Guan Wei in his studio, photograph Luise Guest.

Guan Wei has had the same small studio in Sydney’s Newtown since 1994, but in China artists know there is no certainty in any rented space. Studios are summarily demolished with little notice and no opportunity for negotiation, to make way for new developments. His current large, airy Beijing space, ironically located close to the vast outlet malls filled with the real and fake big-name brands beloved of Chinese shoppers (where he assures me he has never been) is his third studio since his return to China in 2008. Filled with paintings and sculptures from different phases of his life, it is also now the space where he is experimenting with ink painting, screen printing, lithography, and painting on ceramics created with artisans in the famous porcelain centre of Jingdezhen. It is also home to his collection of sketchbooks, filled with intricate drawings and plans for works – paintings, sculptures and the designs he intends to paint onto the new ceramic works. The tiny drawings in these books, delicate and deft in execution, are like storyboards for a film. In some ways his work is cinematic – narrative, often epic in scale, and featuring multiple overlapping plotlines. Guan Wei’s sense of humour, as well as his keen awareness of both Chinese traditional practices and the contemporary artworld underpins his practice. His work is deeply moral, frequently dealing with injustice and repression; yet also calmly reflective, and highly attuned to a sense of the ridiculous. There is a disarming lightness of touch which actually lends greater weight to the seriousness of his purpose.

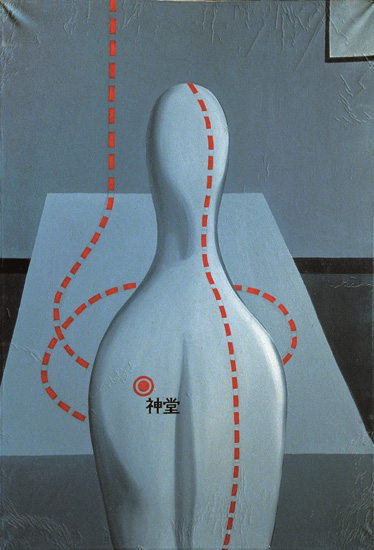

Guan Wei, Acupuncture point - Temple, 1985, oil on canvas, 60 x 75cm. Image courtesy the artist.

His story as a member of that group of artists who made Sydney their refuge after the events of 1989 is well known in Australia. This diasporic personal history plays out in all his work, with its focus on issues of migration, and imagery relating to the journeys of both the colonisers and the dispossessed. It is often assumed that he came to Australia as a direct result of the student uprisings and their culmination at Tiananmen Square in June of 1989. In fact, he arrived in January of that year with artist friends Ah Xian and Lin Chunyan as a result of a chance meeting with Professor Geoff Parr to take up a 2-month residency at the University of Hobart’s Tasmanian School of Art. During that time, he tells me, he completed thirty three paintings in his ‘Acupuncture’ series, working in his early style of grey, black and red with overtly political themes. He realised that Australian audiences, despite their unfamiliarity with contemporary Chinese art at this time, were able to understand his intended meanings and the political concerns about the lack of human rights and democratic freedoms in China that he expressed in these works.

Returning to China in April of that year, despite the concern of his Australian friends, he discovered what was happening with the student pro-democracy demonstrations in Beijing. These events and the resulting repression of artists, writers and intellectuals, made him reconsider his position. He says it made him feel “very badly and sadly about the situation in China, (with) so many intellectuals and students leaving.” In August 1990 Guan Wei returned to Hobart, having been given strong support by numerous individuals including Professor Geoff Parr and Bernice Murphy, at that time Deputy Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, and by the Australian Government. Later, after a year in Hobart, came residences at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, the Canberra School of Art at the Australian National University, and then his productive relationship with Sherman Galleries in Sydney. I wonder aloud what it must have been like for an artist from Beijing to find himself in Hobart, of all places, at the start of the 90s. He laughs and says, “I got two culture shocks. When I arrived in Hobart I got a culture shock; it was so beautiful but so very quiet. After five pm nobody on the streets! When I go back to China after four years (to visit) I got another culture shock because of the pollution. So dirty, even in daytime you could not look clearly. (So) when I went back to Australia I changed my subject. For a couple of years I did a lot (of paintings) about the environment.”

At this time he began to use maps in his work, initially with the idea of creating maps of the apocalypse, and later as a way of exploring ideas about colonisation and nationalism. It was at this time, also, that he began to introduce scientific and biomedical elements into his work, with the ‘Test Tube Babies’ series. Later, he says, “I did a lot of Australian political stories, like refugee and migration stories – mixing indigenous stories and colonisation.” “Are you also thinking of your own journey, and more generally the diasporic experiences of so many Chinese artists in these works?” I ask. “Yes, of course!” he says. Guan Wei points out, though, that he feels a responsibility, living in Australia, to tell Australian stories in his work. “I am different to other Chinese artists living in Australia. My many Chinese artist friends, like Shen Jiawei, are doing Chinese histories, but I am doing Australian histories. If you live in Australia you must serve Australian audiences; that is my opinion. That is why I am interested in Australian history, Australian politics and culture. I did a big show at the Powerhouse Museum called ‘Other Histories’ [2006 ‘Guan Wei’s Fable for a Contemporary World’ was his first foray into large scale mural painting] about the Chinese discovering Australia. It’s maybe not true!” “A parallel ‘Guan Wei’ universe?” I suggest. “Yes!” he says.

His ambitious wall mural, ‘The Journey to Australia’, commissioned for the new entrance to Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art reveals his continuing interest in themes of diaspora and migration. The painting, which shows a fleet of boats heading towards Australian shores, is a pointed reference to the continuing debates about immigration and, in particular, about boat arrivals. He has in the past described his work as a kind of “bearing witness” to these themes. As with other, earlier, paintings, he is interested in layering indigenous history, colonisation, Chinese history and recent political discourses about refugees and border protection. With his distinctive iconography of lyrical floating clouds, map coordinates, and meteorological patterns; and references as diverse as Chinese astrology, necromancy, traditional medicine and 21st century science, he is able to create works which cleverly comment on contemporary paranoia, yet also reflect the universal themes of journeying, so prevalent in ancient Chinese texts, and literati paintings of wandering scholars in misty landscapes of clouds and mountains.

Guan Wei, Subdued Demons vase, 2012. Ceramic, H37cm x Dia20cm. Image courtesy the artist

A recent exhibition in Suzhou, Enigma Space, at No. 8 Gallery in Suzhou Industrial Park, represents a new direction in his practice. Small installations of acrylic paintings on boards include found objects such as rocks, bonsai trees and tea, arranged horizontally on narrow shelves. Referencing the Chinese classical design of the garden as a refuge, a spiritual space for contemplating nature in its most perfect form, these works extend his particular visual language in a more overtly narrative manner. Guan Wei has always worked in series, and the paintings move beyond that convention to create tiny landscape vistas which evoke the experience of reading a Chinese scroll. In the catalogue for this exhibition he says, “In our daily lives gardens provide us refuge and spiritual comfort. They are a wonderland within the physical world.” Like many other contemporary Chinese artists, it seems, Guan Wei is reconsidering the traditions of literati painting and the mastery of representing idealised version of nature with ink and brush. In the chaos and confusion of the contemporary world, the artist is continuing to work with deeply felt ideas about the environment, and about the relationship between man and nature.

Guan Wei, Enigma Place No.1, 2013. Acrylic on board & rock?30 x 200 cm, 8 panels. Image courtesy the artist

Since 1994 Guan Wei has visited China regularly, making the significant decision to set up a studio in Beijing in 2008. “Why return?” I ask. He gives his characteristic laugh and says, “So many reasons.” Firstly, he tells me, the decision was prompted by the transition of Sherman Galleries to its new incarnation as the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation and the fact that he was thus no longer represented (at that time) by a Sydney gallery. Secondly, he was invited to produce works for the cultural component of the Beijing Olympics. Thirdly, he says, “Since 2002, each year when I come back to visit family and friends I see big changes; big art communities; many of my artist friends have big studios. I feel very excited! And many of my Chinese artist friends were already back in China.” And, finally, and perhaps most importantly, he wanted to bring his young daughter back to China, to learn about her Chinese culture and background. And of course, he adds, in Beijing it is easy for him to communicate with colleagues, technicians, fabricators and galleries; he has access to spaces, assistants and materials that would be impossible, or impossibly expensive, in Sydney. This has allowed him to explore new possibilities – the bronzes, the ceramics, the current installation of shelf works in Suzhou, that city of beautiful gardens.

Guan Wei, Ocean, bronze sculpture, 2013. Image courtesy the artist

For his 2013 show at Martin Browne Fine Art, he completed the paintings in Sydney but the bronze sculptures, large and small, were made in China. The complexities and logistics of this kind of global practice are not to be underestimated. In these works too, the complex layering of Chinese and Western references are clear. The solid weighty forms remind me of the female figures of the 19th century sculptor Aristide Maillol, yet their heaviness is belied by the fact that they are frolicking in water, like the pink figures in his paintings which reference the joyful hedonism of Australian beach culture. The stylised water in these bronze works is a reference to the lotus seat of the Tathagata Buddha. The body in water, unencumbered by its own weight, is able to enter a state of complete liberty. His paintings in this show reinforced the palpable awareness of Australia as an island continent, of a place with edges, and permeable borders. Figures cluster on shorelines, or traverse oceans and seas in tiny boats. The series ‘Twinkling Galaxies’ with its emphasis on constellations and heavenly bodies in the endless darkness of the night sky, reveals the sense of place and the careful observation of particular locations that is so evident in his work, as well as his interest in mythology and science. And, as he said to me with a laugh, he always gets a shock when he returns from Sydney to Beijing and realises that he cannot see any stars through the haze of pollution.

At the end of our conversation he is most animated when he shows me the samples of his ceramics from Jingdezhen. It will be too cold during the Chinese winter to go there to continue the project, he says, so he is impatiently waiting for the moment when he can return to work with the porcelain craftsmen and apply his lyrical human figures, demons and mythological creatures to the seductive curved surfaces of the vessels and bowls. Guan Wei is an artist who never stands still. Just as he continues his regular journeying between Beijing and Sydney, so too his work continues to evolve