|

| Zhang Xiaogang at Pace Gallery New York |

I've been a long time away from this blog, I know. Just one more thing to feel guilty about: those nuns taught me well! In any case, self-flagellation aside, my September holiday in New York was so filled with Chinese art that it became what used to be called a 'busman's holiday' (for millennials that means 'a holiday or form of recreation that involves doing the same thing that one does at work.') I am sure there must be a Chinese idiom for this as there is for everything else, but I just don't know that one!

The New York gallery and museum scene was so filled with events and exhibitions relating to China that I wrote this piece for The Art Life. And the focus on Chinese art helped to stop me picking at mental and emotional scabs caused by the hideousness of the Brett Kavanaugh Supreme Court nomination and the fact that Donald Trump was in town.

From solo shows in Chelsea to Song Dynasty shan shui paintings (literally, ‘mountain and water’ and the Chinese term for landscape) at the Metropolitan Museum; from a book launch by celebrated critic and curator Barbara Pollack to One Hand Clapping, young curator Xiaoyu Weng’s latest exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum, New York was most unusually focused on China. The Guggenheim show featured Cao Fei’s evocation of a post-human future, Wong Ping’s fabulously eccentric digital tale of an elderly porno addict and interesting new works by Lin Yilin, Samson Young and Duan Jianyu. The famous koan, ‘one hand clapping’, says the Guggenheim, is a metaphor for how meaning is destabilised in a globalised world.

Following the theme of a globalised world, Brand New Art From China is art critic and curator Barbara Pollack’s second book, following her 2010 Wild Wild East: The Adventures of an American Art Critic in China. Book events to mark its launch were held at two major New York galleries in September. Pollack coined the phrase ‘post-passport generation’ to describe younger artists, often educated outside China, whose eyes are turned firmly to the global rather than the local. They are sometimes categorised as ‘post-80s’, or ‘post-internet’, labels that many detest. They often (but not always) reject obvious tropes of ‘Chineseness’ in favour of an international visual language.

|

| Barbara Pollack and curator Xiaoyu Weng discuss Pollack's book 'Brand New Art From China' at James Cohan Gallery |

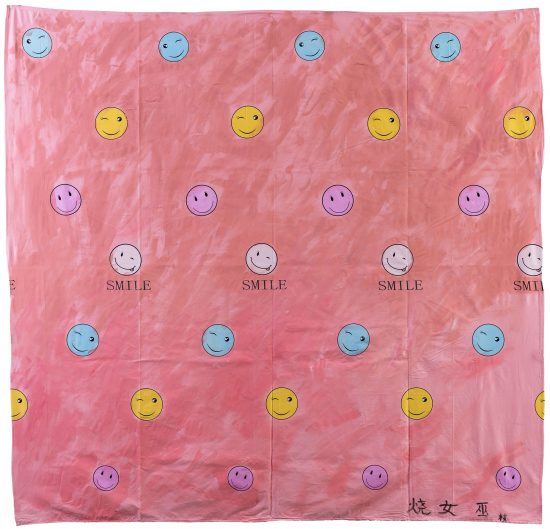

Liao Guohe, Burn Witches, 2018, image courtesy Boers-Li Gallery, New York

This post-Mao generation, whose work has been seen in Sydney in recent exhibitions featuring Sun Xun, Lu Yang, Tianzhuo Chen and Geng Xue, was represented in the New York commercial gallery scene by Liao Guohe. Born in 1977, just after the end of the Cultural Revolution, he is a harbinger of the work of the new generation. Liao has cultivated a constructed persona, deliberately confusing hapless biographers with a CV featuring ‘alternative facts’. He was born in Calcutta, he says – or maybe in Changsha – and educated in California, or maybe not. His deliberately crude canvases and sheets of unstretched fabric in Burn Witches at Boers-Li’s Manhattan space are covered with idiosyncratic symbols and scrawled Chinese characters.

Sometimes described as the chief exponent of ‘bad painting’ in China, Liao’s scatological works are often very funny, but also filled with overwhelming anger at the injustices and absurdities of modern life. Painted mostly on cheap lengths of fabric purchased at Beijing wholesale markets (a response to the third forced demolition of his studio in the constant reconstruction of the city), they feature smiley faces and the repeated character ‘gan’, which may be translated as ‘work’ but is also obscene slang. Like jittery internet memes and the constant contortions of Chinese users of the ‘Chinternet’ to evade government censors, these paintings reflect Chinese society in coded ways.

Sometimes described as the chief exponent of ‘bad painting’ in China, Liao’s scatological works are often very funny, but also filled with overwhelming anger at the injustices and absurdities of modern life. Painted mostly on cheap lengths of fabric purchased at Beijing wholesale markets (a response to the third forced demolition of his studio in the constant reconstruction of the city), they feature smiley faces and the repeated character ‘gan’, which may be translated as ‘work’ but is also obscene slang. Like jittery internet memes and the constant contortions of Chinese users of the ‘Chinternet’ to evade government censors, these paintings reflect Chinese society in coded ways.

Zhang Xiaogang, Mirror No. 2, 2018. Oil on paper with paper and cotton rope collage, 142 x 112 cm, Courtesy of Pace Gallery New York.

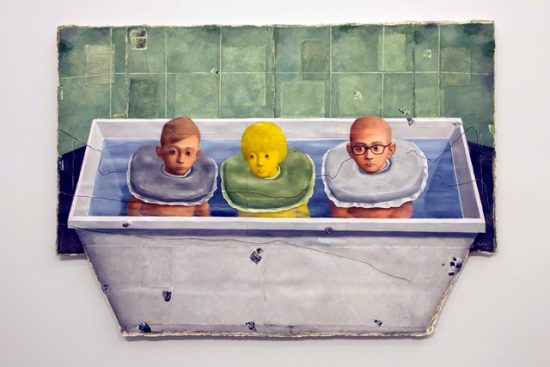

Zhang Xiaogang, Bathtub, 2018. Oil on paper with magazine and cotton rope collage, 144 x 203 cm. Courtesy of Pace Gallery New York

In contrast, Pace Gallery showed new work by Zhang Xiaogang (b. 1958), one of the major figures from the generation of painters who exploded onto the international art market in the 1990s. Political Pop and Cynical Realist artists created bleakly satirical images as a response to their experiences of the Cultural Revolution and their unease at the tidal wave of western influences transforming Chinese society. Sometimes unfairly accused of ‘self-orientalising’, creating an art ‘brand’ to seduce foreign curators and collectors, artists such as Zhang now struggle to break free of socialist imagery. The works in this show, painted on paper with hand-torn, uneven edges and layers of collage, represent that shift. They are still, however, directly related to his famous ‘Bloodline’ series inspired by melancholy family photographs from the Cultural Revolution.

In some cases, Zhang’s earlier work is referenced directly. Mirror No. 2 recalls a locket opened to reveal its secret photographs, or a mirror that reflects a memory. On the right oval a woman, perhaps Zhang Xiaogang’s mother, is painted in sombre monochrome except for the artist’s characteristic patch of translucent red, like a birthmark. On the right a bourgeois chandelier hangs over a bathtub, against a background of mottled wallpaper. The bathtub image recurs too, in a painting depicting three small children seated in a bath filled to the brim, their heads held above rubber rings, their gaze averted. It is a disturbing image, suggesting institutional life in hospitals or orphanages. Another painting depicts thermos flasks of the kind now acquired as nostalgic souvenirs, but once holding hot water in every Chinese home and workplace. For Zhang Xiaogang, the melancholia and recurring memories of the ‘Bloodline’ series remain, even to the threads that meander across the surface of the works.

In some cases, Zhang’s earlier work is referenced directly. Mirror No. 2 recalls a locket opened to reveal its secret photographs, or a mirror that reflects a memory. On the right oval a woman, perhaps Zhang Xiaogang’s mother, is painted in sombre monochrome except for the artist’s characteristic patch of translucent red, like a birthmark. On the right a bourgeois chandelier hangs over a bathtub, against a background of mottled wallpaper. The bathtub image recurs too, in a painting depicting three small children seated in a bath filled to the brim, their heads held above rubber rings, their gaze averted. It is a disturbing image, suggesting institutional life in hospitals or orphanages. Another painting depicts thermos flasks of the kind now acquired as nostalgic souvenirs, but once holding hot water in every Chinese home and workplace. For Zhang Xiaogang, the melancholia and recurring memories of the ‘Bloodline’ series remain, even to the threads that meander across the surface of the works.

Shang Yang, Decayed Landscape No.2, 2018. Mixed media on canvas,122 x 436 cm (48 x 171 3/4 in), Courtesy of the artist and Chambers Fine Art

Shang Yang, Decayed Landscape No.3, 2018, Mixed media on canvas, 168 x 777 cm (66 x 305 1/2 in). Courtesy of the artist and Chambers Fine Art

At Chambers Fine Art a third solo show featured an artist of an older generation. As yet little known outside China, Shang Yang was born in 1942 and graduated from the Hubei Institute of Fine Arts in 1965, where he had been trained in the mandatory Soviet-style Socialist Realism. As an impoverished young artist he could barely afford to buy paint or canvas, prompting his use of found materials and bitumen, a practice he continues. I met Shang in Beijing in April, and in a long conversation over cups of tea in his studio he said, ‘I think, looking back at my career, I have done only two things. One thing is to paint water, one thing is to paint mountains.’

Shang’s large canvases, representing scarred, damaged landscapes, suggest looming environmental disasters. A rich seam of art historical references underpins his mature style; Shang loves Song Dynasty painter Fan Kuan’s lyrical images of mountains and streams, but also references Anselm Kiefer and Cy Twombly. Seamlessly embedding his deep knowledge of Chinese and western art history and aesthetics into his own practice, he works tirelessly in his Beijing studio, driven by dismay and sorrow at the wasteful consumerist society he now inhabits. In April, looking at the canvases arrayed around the walls of his studio, I asked him, ‘Do you see your work as a wake-up call, a warning to humanity about where we are heading if we don’t take heed of our relationship with nature?’ Shang replied: ‘Yes, that is my purpose. I have been focusing on this theme for two or three decades. I want to warn the whole world.’

Shang Yang sees the damage wrought to the natural environment, in China and everywhere, as an irreversible catastrophe. Since the 1990s he has obsessively painted totemic mountains: the Dong Qichang Project series (Dong Qichang Project 38 is now in the White Rabbit Collection) and the Decayed Landscape emerged from his dawning realisation that the rapid transformation of Chinese society into a market economy requiring ever-increasing urbanisation would have unforeseen consequences. Decayed Landscape No.2 reveals Shang’s characteristic syntax of triangular volcano-like forms, the essence of ‘mountain’, like a pictograph. It’s a powerful, minimalist language of form and mark, an almost brutal surface that yet suggests immense sorrow and regret. The empty spaces in Shang’s vast canvases are as important as the dark, brooding mountains.

The work of three artists born into very different periods of modern Chinese history evokes an overwhelming melancholy, as well as an emphatic avowal of the continuing significance of painting in contemporary art. The idea, often expressed now, that the old guard of artists in China are no longer relevant and should move over to make way for new blood strikes false. Shang Yang’s compelling canvases distill a lifetime dedicated to painting, experimentation, teaching, study and clear-eyed observation of his society. Perhaps the last word goes to a collaged paper scrap in one of Zhang Xiaogang’s canvases – a newspaper clipping reporting on Bob Dylan’s 30th anniversary concert at Madison Square Garden, with the headline ‘Forever Young’.

See my other articles in The Art Life HERE

Check back soon: at some point in the near future I'll write about my visit to Lin Yan's studio in Long Island City.

The work of three artists born into very different periods of modern Chinese history evokes an overwhelming melancholy, as well as an emphatic avowal of the continuing significance of painting in contemporary art. The idea, often expressed now, that the old guard of artists in China are no longer relevant and should move over to make way for new blood strikes false. Shang Yang’s compelling canvases distill a lifetime dedicated to painting, experimentation, teaching, study and clear-eyed observation of his society. Perhaps the last word goes to a collaged paper scrap in one of Zhang Xiaogang’s canvases – a newspaper clipping reporting on Bob Dylan’s 30th anniversary concert at Madison Square Garden, with the headline ‘Forever Young’.

See my other articles in The Art Life HERE

Check back soon: at some point in the near future I'll write about my visit to Lin Yan's studio in Long Island City.